|

|

- Search

Abstract

Stereotactic radiosurgery (SR) represents an increasingly utilized modality in the treatment of intracranial and extracranial pathologies. Stereotactic spine radiosurgery (SSR) uses an alternative strategy to increase the probability of local control by delivering large cumulative doses of radiation therapy (RT) in only a few fractions. SSR in the treatment of intramedullary lesions remains in its infancy-this review summarizes the current literature regarding the use of SSR for treating intramedullary spinal lesions. Several studies have suggested that SSR should be guided by the principles of intracranial radiosurgery with radiation doses placed no further than 1-2mm apart, thereby minimizing exposure to the surrounding spinal cord and allowing for delivery of higher radiation doses to target areas. Maximum dose-volume relationships and single-point doses with SSR for the spinal cord are currently under debate. Prior reports of SR for intramedullary metastases, arteriovenous malformations, ependymomas, and hemangioblastomas demonstrated favorable outcomes. In the management of intrame-dullary spinal lesions, SSR appears to provide an effective and safe treatment compared to conventional RT. SSR should likely be utilized for select patient-scenarios given the potential for radiation-induced myelopathy, though high-quality literature on SSR for intramedullary lesions remains limited.

Stereotactic radiosurgery (SR) represents an increasingly utilized treatment for intracranial and extracranial pathologies. Currently, SR is considered a therapeutic adjuvant though its role as a primary intervention continues to be explored. SR was first conceived by Lars Leksell18) as a potential tissue ablation modality in intracranial functional neurosurgery. Further improvements in frameless stereotactic technology allowed for advanced targeting capabilities of spinal lesions.1) During the mid-1990s, investigators sought to expand the scope of SR to extracranial pathology-specifically on spinal tumors. In 1996, Hamilton et al.12) first reported the use of SR for spinal pathology using a linear accelerator (LINAC). More recently, SR was defined as using externally generated ionizing radiation to inactivate or eradicate defined targets in the head or spine performed in a limited number of sessions (up to a maximum of five)2). A recent survey of 551 practitioners of SR highlighted the broad use of stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) in clinical practice in the United States with 67.5% of survey-responders reportedly treating spinal pathology through SBRT22).

Modern microsurgical techniques allow for safe resection of intramedullary spinal tumors8). Postoperative radiation therapy (RT) may aid in reducing tumor recurrence and improving long-term survival in spinal cord ependymomas and astrocytomas14,17). Conventional RT is commonly utilized in the treat ment of spinal cord tumors, especially in conjunction with surgical resection7). Stereotactic spine radiosurgery (SSR) uses an alternative strategy to conventional RT in an effort to help improve local control by delivering large cumulative doses of RT in fewer fractions25,37). Select patient populations may benefit most from SR including those with intramedullary spinal lesions. For example, Ryu et al.27) presented intriguing data on intramedullary spinal tumors treated with SSR-however, comprehensive data of SSR for spinal lesions requires further study.

This review article will summarize the use of SSR for intramedullary spinal lesions.

No consensus definition of radiosurgery exists among neurosurgeons and radiation oncologists. Multiple reports have attempted to clarify, define, or redefine the terms stereotactic radiosurgery (SR) and stereotactic radiotherapy (SRT)2).

Modern LINAC technology is equipped for a wide variety of treatment modalities including intensity-modulated radiation therapy, stereotactic management, and image-guided radiation therapy. Advancements in LINAC technology have made hypofractionation more feasible and have reduced the toxicities associated with administering large fraction sizes11). SBRT can deliver high, ablative radiation doses (typically >5 Gy per fraction) in a limited number of fractions (1-5 fractions) to ≥1 extracranial target(s)3,6,22,28,36).

Historically, SR treatment involved the delivery of a single radiation fraction. However, in 1996, the American Association of Neurological Surgeons (AANS) and the Congress of Neurological Surgeons (CNS) redefined radiosurgery, stating that: SR typically is performed in a single session, using a rigidly attached stereotactic guiding device, other immobilization technology and/or a stereotactic image-guidance system, but can be performed in a limited number of sessions, up to a maximum of five2). However, confusion remains between the terminologies SBRT and SSR, in large part because the term SBRT originated from RT and SSR. Neurosurgeons tend to use SSR over SBRT-therefore, we will use SSR henceforth in this review.

Similar to intracranial SR, SSR delivers an ablative dose of conformal radiation to the target volume with a steep fall-off in dose beyond the treatment region. The development of Gamma-knife radiosurgery and LINAC-based techniques allowed for the delivery of highly conformal doses of radiation within a single fraction6). CyberKnife prototypes from Accuray were first used in the 1990s, and, in 2001, the FDA granted clearance for their use in treating extracranial lesions21). Published reports have suggested that SSR specifications should be guided by the requirements of intracranial radiosurgery - with doses placed no further than 1-2mm apart28). The most commonly utilized SSR machines include Elekta Synergy S, Novalis (Brainlab) and CyberKnife (Table 1)-all employ computed-tomography-based technology for treatment planning. Novalis and CyberKnife also use serial radiographs during SR treatment to account for spine movement and adjust treatment accordingly. Elekta Synergy S and Novalis utilize a mobile table to change targeting coordinates, while Cyber-Knife uses a mobile robotic arm. Data suggest that all systems have excellent accuracy, and additional studies indicate that targeting areas remain accurate to within 1mm5,15,38). For example, CyberKnife was found to have a clini cally relevant accuracy of 0.7-0.3mm5). Overall, such systems minimize radiation exposure to the spinal cord and allow for the relatively safe application of high doses of radiation to target areas39).

A main advantage of SSR over conventional RT lies in the higher biological effective dose (BED) delivered to the tumor or lesion. Through the highly conformal dose-shape surrounding the tumor target, the volume of non-tumor tissue not exposed to radiation is significantly lower in SSR. This aids in reducing acute-onset and late-onset radiation-induced complications and allows for more efficacious, higher target doses for radioresistant tumors13,28,33).

The linear-quadratic model is widely accepted as a predictive tool for quantifying the effects of ionizing radiation on cells and often serves as the basis for determining fractionation schemes6). In general, this model suggests that the severity of the late-responding effects on tissues such as the spinal cord increases with larger fraction sizes. The α and β, respectively, represent coefficients for the non-repairable and repairable components of radiation-induced tissue damage. The constants α and β are defined as the dose where α effects and β effects equal one another. Tissues such as the spinal cord are thought to have a lower α/β ratio (at 3 Gy or less) - a setting where β effects predominate or, said differently, an environment with less irreparable damage and/or greater capacity to repair radiation damage)4). This finding may be attributable, in part, to the low rate of mitosis that neural tissue undergoes or secondary to other repair mechanisms that allow for a greater capacity to repair radiation damage4). Of note, radioresistant tumors like melanoma and sarcoma are believed to have smaller α/β values6).

Although the linear-quadratic model has limitations - including overestimated cell destruction10) - it provides valuable information about tumor control and normal tissue toxicity.19) Radiation triggers a multitude of cellular effects that result in cell death outside the mitotic pathway. Cellular apoptosis is an important component of such processes with research indicating that endothelial apoptosis becomes significant above a single-dose threshold of 8-10Gy6). Radiation effects on tumor vasculature and tumor hypoxia also likely play a role in tumor responsiveness. Other critical mechanisms of cellular and tissue behavior that contribute to radiation response have yet to be elucidated.

SR appears particularly suitable for parallel, glandular organs like lung, kidney, and liver with structurally distinct subunits6). Serial functioning tissues from linear or branching organs like the spinal cord, esophagus, bronchi, and bowel with undefined subunits may also benefit from reduced high-dose volume though the applications are less studied. Concern exists for ablating tissue like the spinal cord given the potential for irreversible downstream effects following damage to upstream portions of the organ6). Small volumes of serially functioning tissues such as the spinal cord likely can receive suprathreshold radiation doses, though the appropriate volume and anatomical regions to safely target have not been well characterized nor has the impact of inhomogeneous dose delivery6,16,19).

Permanent, radiation-induced myelopathy signifies the gravest concern for using SSR in intramedullary spinal lesions. When it occurs, permanent radiation-induced myelopathy typically has severe effects as normal tissues are more sensitive to the high-dose-per-fraction radiation. Case reports have documented paralysis secondary to permanent radiation-induced myelopathy - underscoring a devastating outcome associated with this technique6,13,20,24,29).

Radiation-induced myelopathy has been reported in patients treated with SSR but with no history of prior radiation exposure30). This is a significant consideration when choosing SSR as the risk of radiation-induced myelopathy for conventional RT is nearly zero with 30Gy of radiation delivered in 10 fractions. For fractionated radiation at 2Gy per fraction, a homogenous dose of 45Gy results in less than a 0.5% risk of radiation-induced myelopathy32). For single fraction radiotherapy, spinal cord tissue tolerance remains unknown but has been estimated at 8-10Gy for homogeneous exposure32). Interestingly, the cauda equina appears to be more tolerant than the spinal cord to SSR-similar to conventionally fractionated radiation-though the SSR doses that result in cauda equina injury have not been fully characterized6,32).

Limits on spinal cord dosing have been published based mos tly on 5 cases of radiation-induced myelopathy with SSR. In those patients, the thecal sac was defined as the avoidance structure. Radiation-induced myelopathy was observed at maxi mum point doses of 25.6Gy in 2 fractions, 30.9Gy in 3 fractions as well as 14.8, 13.1, and 10.6Gy in 1 fraction30,31). The authors concluded that 10 Gy in a single fraction was safe and suggested that a normalized 2-Gy-equivalent BED of 35Gy delivered in up to 5 fractions carried a low risk of radiation-induced myelopathy30). This translated to a maximum dose of 14.5Gy in 2 fractions, 17.5Gy in 3 fractions, 20 Gy in 4 fractions, and 22Gy in 5 fractions administered to a point within the thecal sac16,30). According to recent data on SSR, a maximum spinal cord dose of 13Gy in a single fraction or 20 Gy in 3 fractions appears to be associated with a <1% risk of injury.16) The decision to use higher doses must weigh the benefit of tumor control against the potential for radiation toxicity.28)

The maximum dose-volume relationship and single-point dose tolerated by the spinal cord are unknown and currently under debate. Ryu et al.26) reported that the partial volume tolerance of the spinal cord is ≥10Gy to 10% of the total spinal cord volume (with spinal cord volume defined as 6mm superior and inferior to the radiosurgery target). Dose constraints for SSR are described in the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) Protocol #0631 comparing SR to conventional RT and are as follows: (1) for spinal cord (contoured, from a fused MRI scan, 5 to 6mm cranial and caudal to the target), 10% to receive <10Gy, 0.35mL <10Gy, and 0.035mL <14 Gy; and (2) for cauda equina, 5mL <14 Gy and 0.035mL <16 Gy. However, insufficient long-term data prevent calculation of a dose-volume relationship for radiation-induced myelopathy when the partial cord was treated with a hypofractionated regimen6).

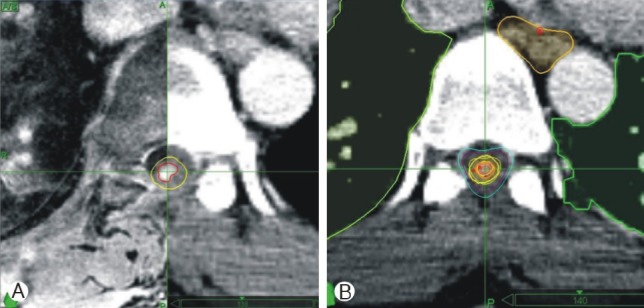

Several features of SSR underscore the importance of appropriate imaging. First, SSR creates highly conformal dose distributions intended to target the tumor and avoid critical structures, thereby necessitating accurate target and normal tissue delineation. Second, steep dose gradients demonstrate that appropriate dosing can vary from an acceptable range to exceeding tolerance based on only 1-2mm changes in distance28). Taken together, SSR requires accurate pre-treatment planning and delivery, requirements serviced by high-quality imaging (Fig. 1).

A planning computed tomography (CT) scan is performed with the patient in treatment position and immobilized, if necessary. CT slice thickness typically is <3mm. Intravenous contrast can be used for improve tumor characterization - however, CT is suboptimal for visualizing the spinal cord and intramedullary lesions as mean spinal cord volumes have been shown to be inaccurately larger with CT scans than with MRI data28). CT-MRI image fusion further improves treatment planning, though the optimal approach to radiographically contour neural tissues in the spinal remains a matter of debate.

Gross tumor volume (GTV) is defined as the radiographically visible tumor based on the fused CT-MRI images6). In intramedullary lesions, no clinical target volume (CTV) is applied and, thus, CTV=GTV. Planning target volume (PTV) can be expanded by 2-3mm beyond the CTV. CTV-PTV expansion accounts for potential errors in patient setup, organ motion, and any mechanical inaccuracy of image-guided treatment delivery. Therefore, CTV-PTV respects dose limits to the spinal cord while keeping within the goal to alleviate patient symptoms and minimize risk of radiation-induced myelopathy6).

On treatment day, patients should be placed supine on a vacuum bag. Setup images are then taken from the image-guided radiotherapy system with any errors corrected prior to treatment. Coregistered images are then evaluated by the treating physician. Repositioning is performed if there is >2 mm difference between pre-treatment images and treatment images and/or if there is rotation >2 degrees (depending on the geometric margins used in the treatment plan)6).

Delayed myelopathy after radiosurgery is uncommon. Many articles cite a case series of 6 patients treated with radiosurgery who developed delayed myelopathy6,9,16). Myelopathic symptoms in all patients were initially managed with corticosteroids. Some patients also received a combination of vitamin E and pentoxifylline (Trental; Sanofi Aventis, Bridgewater, NJ), hyperbaric oxygen, gabapentin (Neurontin; Pfizer, New York), and/or physical therapy. Following treatment, 3 of the 6 patients' myelopathic symptoms improved, 2 patients reached a clinical plateau, and 1 patient progressed to paraplegia. Of the 3 patients who improved clinically, follow-up MRI scans revealed complete radiographic resolution of their spinal cord edema9).

In 2009, Parikh and Heron23) reported a case of metastatic renal cell carcinoma in the intramedullary area of C5 treated with SSR using a dose of 15 Gy in 3 fractions to the 80% isodose line. At 26 months following treatment, the patient was alive, fully functional, and reported no pain with rare paresthesias. In 2009, Shin et al34). reported data from 4 intradural extramedullary spinal tumors and 7 intramedullary metastases all treated with SSR using image-guided and intensity-modulated radiation. Mean treatment dose was 13.8Gy (range: 10-16Gy), and median follow-up duration was 10 months. Of those patients with intramedullary metastases, 5 patients improved clinically, 1 patient was unchanged, and 1 patient was lost to follow-up. Table 2 includes further details on the studies mentioned above.

In 2006, Sinclair et al.35) published 15 cases of intramedullary arteriovenous malformations (AVM) treated with CyberKnife technology - of those patients studied, 7 received embolization before radiosurgery. Mean dose of 20.5Gy was delivered to the margin of the AVM nidus in 2-5 fractions to decrease the risk of radiation-related spinal cord damage. Up to 3 years post-radiosurgery follow-up data was available. Complete angiographic obliteration after radiosurgery was seen in 1 patient, and 4 patients showed evidence of residual AVM on angiography (although AVM volumes were significantly reduced). Remaining patients did not undergo final angiography but showed significant AVM volume reduction on MRI. None of the patients demonstrated evidence of hemorrhage or neurological deterioration attributable to SSR (Table 2).

In 2003, Ryu et al.27) discussed 7 hemangioblastomas and 3 ependymomas treated with CyberKnife. Patients had either recurrent tumors, undergone several previous surgeries, possessed medical contraindications to surgery, and/or declined open resection. Conformal treatment planning prescribed doses of 18-25Gy to the lesions in 1-3 stages. No significant treatment-related complications were recorded. Mean radiographic and clinical follow-up duration was 12 months (range: 1-24 months). On follow-up neuroimaging, 1 ependymoma and 2 hemangioblastomas were smaller-remaining tumors remained stable in size (Table 2).

In the management of intramedullary spinal lesions, SSR appears to provide an effective and safe alternative treatment option to conventional RT. However, the available literature on SSR for intramedullary spinal lesions remains limited, and proper spinal cord dosing in SSR has yet to be clarified. Therefore, SSR should be employed for select cases given the increased potential for radiation-induced myelopathy with higher-dose-per-fraction radiation. SSR in the treatment of intramedullary spinal lesions will continue to improve over time as image-guided systems deliver safer and more effective radiation therapy.

References

1. Adler JR Jr, Murphy MJ, Chang SD, Hancock SL. Image-guided robotic radiosurgery. Neurosurgery 1999 44:1299. -1306. discussion 1306-1307. PMID: 10371630.

2. Barnett GH, Linskey ME, Adler JR, Cozzens JW, Friedman WA, Heilbrun MP, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery--an organized neurosurgery-sanctioned definition. J Neurosurg 2007 106:1-5. PMID: 17240553.

3. Benedict SH, Yenice KM, Followill D, Galvin JM, Hinson W, Kavanagh B, et al. Stereotactic body radiation therapy: the report of AAPM task group 101. Med Phys 2010 37:4078-4101. PMID: 20879569.

4. Bentzen SM, Thames HD, Travis EL, Ang KK, Van der Schueren E, Dewit L, et al. Direct estimation of latent time for radiation injury in late-responding normal tissues: gut, lung, and spinal cord. Int J Radiat Biol 1989 55:27-43. PMID: 2562974.

5. Chang SD, Main W, Martin DP, Gibbs IC, Heilbrun MP. An analysis of the accuracy of the cyberKnife: a robotic frameless stereotactic radiosurgical system. Neurosurgery 2003 52:140. -146. discussion 146-147. PMID: 12493111.

6. Chawla S, Schell MC, Milano MT. Stereotactic body radiation for the spine: a review. Am J Clin Oncol 2011.

7. Dahele M, Zindler JD, Sanchez E, Verbakel WF, Kuijer JP, Slotman BJ, et al. Imaging for stereotactic spine radiotherapy: clinical considerations. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2011 81:321-330. PMID: 21664062.

8. Gezen F, Kahraman S, Canakci Z, Beduk A. Review of 36 cases of spinal cord meningioma. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000 25:727-731. PMID: 10752106.

9. Guerrero M, Li XA. Extending the linear-quadratic model for large fraction doses pertinent to stereotactic radiotherapy. Phys Med Biol 2004 49:4825-4835. PMID: 15566178.

10. Haley ML, Gerszten PC, Heron DE, Chang YF, Atteberry DS, Burton SA. Efficacy and cost-effectiveness analysis of external beam and stereotactic body radiation therapy in the treatment of spine metastases: a matched-pair analysis. J Neurosurg Spine 2011 14:537-542. PMID: 21314284.

11. Hamilton AJ, Lulu BA, Fosmire H, Gossett L. LINAC-based spinal stereotactic radiosurgery. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg 1996 66:1-9. PMID: 8938925.

12. Hsu W, Nguyen T, Kleinberg L, Ford EC, Rigamonti D, Gokaslan ZL, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery for spine tumors: review of current literature. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg 2010 88:315-321. PMID: 20714211.

13. Isaacson SR. Radiation therapy and the management of intramedullary spinal cord tumors. J Neurooncol 2000 47:231-238. PMID: 11016740.

14. Kim S, Jin H, Yang H, Amdur RJ. A study on target positioning error and its impact on dose variation in image-guided stereotactic body radiotherapy for the spine. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2009 73:1574-1579. PMID: 19306754.

15. Kirkpatrick JP, van der Kogel AJ, Schultheiss TE. Radiation dose-volume effects in the spinal cord. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010 76:S42-S49. PMID: 20171517.

16. Kopelson G, Linggood RM, Kleinman GM, Doucette J, Wang CC. Management of intramedullary spinal cord tumors. Radiology 1980 135:473-479. PMID: 7367644.

17. Leksell L. The stereotaxic method and radiosurgery of the brain. Acta Chir Scand 1951 102:316-319. PMID: 14914373.

18. Milano MT, Constine LS, Okunieff P. Normal tissue toxicity after small field hypofractionated stereotactic body radiation. Radiat Oncol 2008 3:36PMID: 18976463.

19. Milano MT, Usuki KY, Walter KA, Clark D, Schell MC. Stereotactic radiosurgery and hypofractionated stereotactic radiotherapy: normal tissue dose constraints of the central nervous system. Cancer Treat Rev 2011 37:567-578. PMID: 21571440.

20. Nomura R, Suzuki I. [CyberKnife radiosurgery--present status and future prospect]. Brain Nerve 2011 63:195-202. PMID: 21386119.

21. Pan H, Simpson DR, Mell LK, Mundt AJ, Lawson JD. A survey of stereotactic body radiotherapy use in the united states. Cancer 2011 117:4566-4572. PMID: 21412761.

22. Parikh S, Heron DE. Fractionated radiosurgical management of intramedullary spinal cord metastasis: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2009 111:858-861. PMID: 19640634.

23. Pirzkall A, Lohr F, Rhein B, Hoss A, Schlegel W, Wannenmacher M, et al. Conformal radiotherapy of challenging paraspinal tumors using a multiple arc segment technique. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2000 48:1197-1204. PMID: 11072179.

24. Rades D, Lange M, Veninga T, Stalpers LJ, Bajrovic A, Adamietz IA, et al. Final results of a prospective study comparing the local control of short-course and long-course radiotherapy for metastatic spinal cord compression. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2011 79:524-530. PMID: 20452136.

25. Ryu S, Jin JY, Jin R, Rock J, Ajlouni M, Movsas B, et al. Partial volume tolerance of the spinal cord and complications of single-dose radiosurgery. Cancer 2007 109:628-636. PMID: 17167762.

26. Ryu SI, Kim DH, Chang SD. Stereotactic radiosurgery for hemangiomas and ependymomas of the spinal cord. Neurosurg Focus 2003 15:E10PMID: 15323467.

27. Sahgal A, Bilsky M, Chang EL, Ma L, Yamada Y, Rhines LD, et al. Stereotactic body radiotherapy for spinal metastases: current status, with a focus on its application in the postoperative patient. J Neurosurg Spine 2011 14:151-166. PMID: 21184635.

28. Sahgal A, Larson DA, Chang EL. Stereotactic body radiosurgery for spinal metastases: a critical review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008 71:652-665. PMID: 18514775.

29. Sahgal A, Ma L, Gibbs I, Gerszten PC, Ryu S, Soltys S, et al. Spinal cord tolerance for stereotactic body radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010 77:548-553. PMID: 19765914.

30. Sahgal A, Ma L, Weinberg V, Gibbs IC, Chao S, Chang UK, et al. Reirradiation human spinal cord tolerance for stereotactic body radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012 82:107-116. PMID: 20951503.

31. Schultheiss TE, Kun LE, Ang KK, Stephens LC. Radiation response of the central nervous system. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1995 31:1093-1112. PMID: 7677836.

32. Sheehan JP, Shaffrey CI, Schlesinger D, Williams BJ, Arlet V, Larner J. Radiosurgery in the treatment of spinal metastases: tumor control, survival, and quality of life after helical tomotherapy. Neurosurgery 2009 65:1052. -1061. discussion 1061-1062. PMID: 19934964.

33. Shin DA, Huh R, Chung SS, Rock J, Ryu S. Stereotactic spine radiosurgery for intradural and intramedullary metastasis. Neurosurg Focus 2009 27:E10PMID: 19951053.

34. Sinclair J, Chang SD, Gibbs IC, Adler JR Jr. Multisession Cyber-Knife radiosurgery for intramedullary spinal cord arteriovenous malformations. Neurosurgery 2006 58:1081. -1089. discussion 1081-1089. PMID: 16723887.

35. Sohn S, Chung CK. The role of stereotactic radiosurgery in metastasis to the spine. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 2012 51:1-7. PMID: 22396835.

36. Timmerman RD, Kavanagh BD, Cho LC, Papiez L, Xing L. Stereotactic body radiation therapy in multiple organ sites. J Clin Oncol 2007 25:947-952. PMID: 17350943.

37. Yan H, Yin FF, Kim JH. A phantom study on the positioning accuracy of the novalis body system. Med Phys 2003 30:3052-3060. PMID: 14713071.

38. Yu C, Main W, Taylor D, Kuduvalli G, Apuzzo ML, Adler JR Jr. An anthropomorphic phantom study of the accuracy of cyber-knife spinal radiosurgery. Neurosurgery 2004 55:1138-1149. PMID: 15509320.

Fig. 1

Images from recurrent intramedullary metastatic cancer at T7 status-post resection, illustrating pre-treatment CT image fusion with MRI scan for contouring (A: CTV and spinal cord demarcated as red and yellow lines, respectively) as well as the ultimate planning image for treatment (B). Of note, radiation dose was 18 Gy in 3 fractions to the 80% isodose line.

Table 1.

Commercially available radiation therapy technologies

Table 2.

Reports of stereotactic spinal radiosurgery (SSR) for intramedullary lesions

| Study (Year) | # of patients/lesions | Disease (s) | System & radiation dose (Gy/Fx) | Follow-up (Months) | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ryu et al.27) (2003) | 7/10 | Hemangioblastoma (n=7), ependymoma (n=3) | CyberKnife 18-25/1-3 | 1-24 | Improved (n=2), stable (n=4), declined (n=1) |

| Sinclair et al.35)(2006) | 15/15 | Arteriovenous malformation (AVM) | CyberKnife 20.5/2-5 | 3-59 | Size reduction (n = 13), completeobliteration (n = 1), clinicallyimprovedorstabilized (92.3%), e-bleeding (n=0) |

| Parikh et al.23) (2009) | 1/1 | Metastatic renal cell cancer | CyberKnife 15/3 | 26 | Clinical improvement (n = 1) |

| Shin et al.34) (2009) | 6/6 | Metastasis (melanoma: n=1; breastcancer: n=2; CA; lungcancer: n=3glioma: n=1) | Novalis 10-16/1 | 2.2-19.4 | Clinical improvement (n=5), unchanged (n=1) |

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

-

- 10 Crossref

- Scopus

- 7,303 View

- 100 Download

- Related articles in NS

-

Transoral Robotic-Assisted Neurosurgery for Skull Base and Upper Spine Lesions2024 March;21(1)

Recent Molecular and Genetic Findings in Intramedullary Spinal Cord Tumors2022 June;19(2)

Review of Photoacoustic Imaging for Imaging-Guided Spinal Surgery2018 December;15(4)

-

Journal Impact Factor 3.2