|

|

- Search

Abstract

Horner syndrome (HS) occurs when there is interruption of the oculosympathetic pathway. The causes of HS are various, but HS originated from herniated cervical disc is very few. HS attributable to the lesion of the first-order neuron of cervical spinal cord is extremely rare. A 41-year old male was admitted for sudden onset of left ptosis and right side numbness. Neurological examination revealed ptosis, miosis and facial anhidrosis on the left side. MRI and CT scans demonstrated large left paramedian disc herniation with cord compression at the C4-5 level. The herniated disc was removed through anterior approach and his symptoms were improved after the operation.

Horner syndrome (HS) was characterized first in humans by Johann Friedrich Horner in 186911). HS results from interruption of the oculosympathetic pathway at anywhere along its course between the hypothalamus and the orbit1). HS is characterized by the classic triad of ipsilateral eyelid ptosis, miosis and facial anhidrosis. There are many causes of HS, but herniated cervical disc (HCD) is a very rare cause among them. HCD is a common cause of spinal cord compression, but HS associated with HCD has been described just in very few literatures. There were only two cases of herniated thoracic disc at T1-2 as the causes of HS2,6). In addition, the occurrence of HCD as the etiology of HS has not been reported. Thus, this study describes extremely rare case of HS associated with HCD.

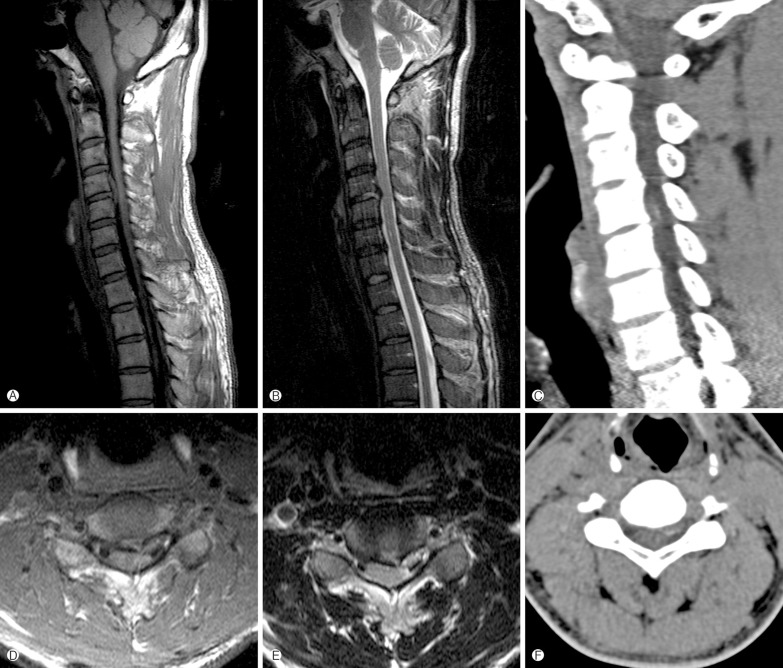

A 41-year old male patient awoke to find sudden onset of left ptosis, right side numbness without identifiable history of trauma or physical stress. He first visited local medical center and had brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) taken, however, no specific findings were found. When he was referred to our neurosurgery department via emergent department, neurological examination presented left side ptosis, miosis and anhidrosis of left half of face which are typical symptoms of HS, and there was numbness below right side of the T8 dermatome. We consulted department of ophthalmology and confirmed left ptosis and miosis (Fig. 1). In darkness, pupils measured 5 mm on the right eye and 3 mm on the left eye, and the left pupil showed dilatation lag. There was 2 mm of left ptosis. Sweat test showed only right side starch powder on the face changed to dark brown color, which means left side anhidrosis (Fig. 1). The cervical spine MRI demonstrated an upward migrated and large left paramedian disc herniation with severe unilateral spinal cord compression at the C4-C5 level which is high signal intensity with internal low signal intensity on T2WI and intermediate signal intensity on T1WI. And extruded disc revealed some high density in cervical spine computed tomography (Fig. 2). As large disc herniation with cartilaginous endplate fragments was doubted, we conducted a standard microsurgical anterior approach to the C4-C5 interspace on 2 days after admission. Posterior longitudinal ligament had been ruptured and spinal cord was severely compressed especially at left side. The extruded disc material was migrated to upward including part of the cartilaginous endplate. After complete decompression of neural structures, anterior cervical fusion was performed with a cage filled with an allograft bone chip. Postoperatively, right side numbness was improved but left miosis and ptosis remained until discharge. However, after two months from the operation, miosis, ptosis and anhidrosis were completely recovered, too.

Horner syndrome, or oculosympathetic paralysis, was characterized first in humans by Johann Friedrich Horner in 186911). It is resulted from interruption of the oculosympathetic pathway between the hypothalamus and the orbit. The clinical findings of HS include ipsilateral miosis, ptosis, and facial anhidrosis1).

The oculosympathetic pathway begins with a first-order neuron at the posterior lateral aspect of the hypothalamus and through the brain stem extends down the spinal cord from C8 to T2. Second-order (preganglionic) neuron, which is located in the intermediolateral gray substance of the spinal cord at the level C8-T2 (Ciliospinal Center of Budge-Waller), then exit the spinal cord via the ventral roots and enter the paravertebral sympathetic chain. The preganglionic pathway passes over the apex of the lung and ascends in the cervical sympathetic chain to the superior cervical ganglion. The third-order (postganglionic) neuron, which is superior cervical ganglion located at the level of C2-C3, posterior to the carotid sheath and anterior to the longus colli muscle, follow the carotid plexus into the skull, join with the ophthalmic nerve, and enter the orbit. HS may occur as a result of injury anywhere along this pathway1,5,9).

Based on localization of the oculosympathetic pathway interruption, a HS is often classified as central (first-order neuron), preganglionic (second-order neuron) or postganglionic (third-order neuron).

The causes of central HS are brain stem ischemia, brain tumors, demyelinating diseases, syringomyelia and transverse myelitis1,4). Preganglionic HS is resulting from thoracic or neck tumor, direct spinal cord trauma, herniated disc at C8-T1, iatrogenic disruption of the sympathetic pathway from radical neck dissection or selective nerve root block, carotid angiography, stenting or endarterectomy, spontaneous carotid dissection, and aortic aneurysm to various malignant conditions that directly or indirectly affect the normal sympathetic innervations3,5,7,8,9,10,12,13). The preganglionic type is most often caused by a tumor or trauma. The causes of postganglionic HS are vascular headaches, tumor or aneurysm in cavernous sinus, nasopharyngeal tumor, and trauma with basal skull fracture. And most frequently it is seen as a consequence of carotid artery dissection or during cluster headache. However, many postganglionic lesions are idiopathic. Anhidrosis is rarely conspicuous, and in the postganglionic subtype, it is virtually absent1,9). Central HS is uncommonly encountered in isolation. In the spinal cord, the fibers of first-order neurons travel in Budge's center immediately lateral to the dorsal gray matter and synapse in the spinal cord gray matter9).

The possible cause of HS in this case is that the HCD directly compresses spinal cord producing an insult to the first-order neuron of the sympathetic pathway within the spinal cord at the level of C4-C5.

MR imaging is the most reliable investigative procedure and should be accepted as an initial diagnostic tool for HS associated with HCD.

Patients with HCD commonly have neck pain, cervical radiculopathy, myelopathy and a combination of these symptoms. However, when patients have no cervical symptoms initially, or completely lack cervical symptoms, this unusual presentation can lead to a delayed or incorrect diagnosis in many wrong directions. In particular, as the patient had no cervical symptoms initially, the physician suspected a cerebral stroke first. Careful history-taking and detailed neurologic examinations are indispensable steps for early diagnosis of HS associated with HCD. For the treatment of it, early diagnosis and prompt surgical decompression is necessary because the significant cord compression will bring about further neurological deficits.

Careful history-taking and detailed neurologic examinations are indispensable steps for early diagnosis of HS associated with HCD. For the treatment of it, early diagnosis and prompt surgical decompression is necessary because the significant cord compression will bring about further neurological deficits.

References

1. Amonoo-Kuofi HS. Horner syndrome revisited: with an update of the central pathway. Clin Anat 1999 12:345-361. PMID: 10462732.

2. Gelch MM. Herniated thoracic disc at T1-2 level associated with Horner's syndrome. J Neurosurg 1978 48:128-130. PMID: 619013.

3. Kaplowitz K, Lee AG. Horner syndrome following a selective cervical nerve root block. J Neuroophthalmol 2011 31:54-55. PMID: 20847700.

4. Kerrison JB, Biousse V, Newman NJ. Isolated Horner's syndrome and syringomyelia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000 69:131-132. PMID: 10864622.

5. Lee JH, Lee HK, Lee DH, Choi CG, Kim SJ, Suh DC. Neuroimaging strategies for three types of Horner syndrome with emphasis on anatomic location. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2007 188:W74-W81. PMID: 17179330.

6. Lloyd TV, Johnson JC, Paul DJ, Hunt W. Horner's syndrome secondary to herniated disc at T1-T2. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1980 134:184-185. PMID: 6766018.

7. Miura J, Doita M, Miyata K, Yoshiya S, Kurosaka M, Yamamoto H. Horner's syndrome caused by a thoracic dumbbellshaped schwannoma: sympathetic chain reconstruction after a one-stage removal of the tumor. Spine 2003 28(2):33-36. PMID: 12544952.

8. Montgomery DM, Brower RS. Cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Clinical syndrome and natural history. Orthop Clin North Am 1992 23:487-493. PMID: 1620540.

9. Reede DL, Garcon E, Smoker WR, Kardon R. Horner's syndrome: clinical and radiographic evaluation. Neuroimaging Clin N Am 2008 18:369-385. PMID: 18466837.

10. Russell JH, Joseph SJ, Snell BJ, Jithoo R. Brown-Sequard syndrome associated with Horner's syndrome following a penetrating drill bit injury to the cervical spine. J Clin Neurosci 2009 16:975-977. PMID: 19386500.

11. van der Wiel HL. Johann Friedrich Horner (1831-1886). J Neurol 2002 249:636-637. PMID: 12021960.

13. Zhao CQ, Jiang SD, Jiang LS, Dai LY. Horner Syndrome due to a solitary osteochondroma of C7: a case report and review of the literature. Spine 2007 32(16):471-474. PMID: 17304140.

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

-

- 7 Crossref

- Scopus

- 7,090 View

- 72 Download

- Related articles in NS

-

Sudden Paraplegia Caused by Nontraumatic Cervical Disc Rupture: A Case Report2017 December;14(4)

Chronic Spinal Epidural Hematoma due to Repeated Epidural Block: A Case Report.2008 March;5(1)

Vertebral Pheochromocytoma of the Cervical Spine - A Case Report -2006 December;3(4)

-

Journal Impact Factor 3.2