What Can Legacy Patient-Reported Outcome Measures Tell Us About Participation Bias in Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Scores Among Lumbar Spine Patients?

Article information

Abstract

Objective

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) is a validated tool for assessing patient-reported outcomes in spine surgery. However, PROMIS is vulnerable to nonresponse bias. The purpose of this study is to characterize differences in patient-reported outcome measure scores between patients who do and do not complete PROMIS physical function (PF) surveys following lumbar spine surgery.

Methods

A prospectively maintained database was retrospectively reviewed for primary, elective lumbar spine procedures from 2015 to 2019. Outcome measures for Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), visual analogue scale (VAS) back & leg, Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), and 12-item Short Form health survey physical composite summary (SF-12 PCS) were recorded at both preoperative and postoperative (6 weeks, 12 weeks, 6 months, 1 year, 2 years) timepoints. Completion rates for PROMIS PF surveys were recorded and patients were categorized into groups based on completion. Differences in mean scores at each timepoint between groups was determined.

Results

Eight hundred nine patients were included with an average age of 48.1 years. No significant differences were observed for all outcome measures between PROMIS completion groups preoperatively. Postoperative PHQ-9, VAS back, VAS leg, and ODI scores differed significantly between groups through 1 year (all p < 0.05). SF-12 PCS differed significantly only at 6 weeks (p = 0.003).

Conclusion

Patients who did not complete PROMIS PF surveys had significantly poorer outcomes than those that did in terms of postoperative depressive symptoms, pain, and disability. This suggests that patients completing PROMIS questionnaires may represent a healthier cohort than the overall lumbar spine population.

INTRODUCTION

As the frequency of spinal procedures has steadily increased, so too has the use of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs). Legacy PROMs such as the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), visual analogue scale (VAS) and the 12-item Short Form health survey (SF-12) measure perceptions of pain, disability, and physical function (PF), but are dated in their ability to provide more personalized assessment. More recent metrics such as the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) utilize computer adaptive testing which customizes questions based on previous responses and provides more efficient and focused assessments of patient-reported outcomes (PROs). Additionally, PROMIS surveys have demonstrated minimal floor and ceiling effects, and their use among spine patients is well-validated [1-4].

Although PROs are of utmost importance to accurately track postoperative improvement, noncompliance is nearly inevitable with any self-report measure and bias may be thereby introduced. Participation bias (also known as nonresponse bias) can occur when there are significant differences between respondents and nonrespondents and may lead to an inaccurate representation of the population at large. Previous studies have demonstrated several important differences between respondents and nonrespondents to PROM surveys. Parrish et al. [5] examined demographic and perioperative variables as predictors of survey completion and reported that patients of African-American or Hispanic race and those with radicular pain were less likely to complete surveys. Conversely, older individuals and patients with more severe depressive symptoms were more likely to complete PROMIS PF questionnaires. Furthermore, several other studies demonstrated higher completion rates among older individuals, and those with postoperative complications, whereas male sex, younger age, lower socioeconomic status and non-White race were reported as predictors of decreased compliance [6-8].

The variability in demographics and perioperative characteristics that may predict respondent and nonrespondent status may have implications for the outcomes experienced by these patients as well. If key differences in PROs exist between respondents and nonrespondents, the data obtained by these surveys may be unrepresentative of the patient population as a whole and, if taken at face value, may misguide clinical decision making or lead some patients to receive inappropriate or inadequate care. Given that it is predicated on the absence of data, participation bias is inherently difficult to quantify. Several orthopedic studies have employed different tactics, such as telephone outreach, to quantify outcomes in nonrespondents [9-11]. One avenue to elucidate PROM trends in nonrespondents that has not been well explored is the use of data from “partial-respondents” who may have completed other PROMs, but not PROMIS PF. The establishment of strong correlations between PROMIS PF and VAS, ODI, and SF-12 at multiple timepoints for both lumbar and cervical spine patients may allow for an alternative route to quantify outcome measures of nonrespondents [2,3,12]. More specifically, use of completed legacy PROMs to extrapolate important data about potential PROMIS scores could provide insight to the true status of postoperative PF among nonrespondents. As the popularity and applications of PROMIS surveys continue to expand, it becomes more important than ever to quantify the impact of participation bias on their results. This study aims to explore the extent of participation bias for PROMIS PF in a cohort of lumbar spine patients by analyzing differences in legacy PROM scores between PROMIS respondents and nonrespondents.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Patient Population

Prior to study onset, this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Rush University Medical Center (ORA #14051301) and written informed consent were obtained from patients. A private registry of prospectively maintained spine surgery data was retrospectively reviewed for patients that underwent primary, elective lumbar spine procedures, which included fusions, decompressions, and discectomies between the dates of May 2015 and July 2019. Revision procedures along with surgeries indicated for traumatic, infectious, or malignant etiologies were excluded.

2. Data Collection

The following patient demographic characteristics were collected: age, sex, body mass index (BMI), preoperative smoking status, diabetic status, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), ethnicity, and insurance/payment type received. Preoperative spinal pathologies were classified as herniated nucleus pulposus (new-onset or recurrent), degenerative spondylolisthesis, isthmic spondylolisthesis, and scoliosis. Perioperative characteristics were recorded including operative duration (in minutes), estimated blood loss (EBL; in mL), and postoperative length of stay (in hours). PROMs assessing pain (VAS back and leg), disability (ODI), PF (SF-12 physical component summary [SF-12 PCS]), and depressive symptoms (Patient Health Questionnaire-9 [PHQ-9]) were collected at preoperative and 6-week, 12-week, 6-month, and 1-year postoperative timepoints. All PROMs were completed either during clinic appointments using a hand-held tablet device or remotely using the patients’ personal devices through an online portal. Patients completing PROMs during clinic appointments were required to finish surveys before meeting with clinicians to avoid any biases.

3. Statistical Analysis

All statistical tests and calculations were performed using Stata 16.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Descriptive statistics were reported for patient demographic characteristics, preoperative spinal diagnoses, and perioperative variables. Perioperative variables were reported separately for patients who underwent lumbar fusion and patients who underwent lumbar decompression/discectomy. Outlier analysis was performed to identify patients with operative duration, EBL, or length of stay > 3 standard deviations above or below the mean value. Outliers were excluded to limit the amount of bias introduced by highly atypical cases. Patients were categorized at each timepoint as PROMIS respondents or nonrespondents based on whether they had completed a PROMIS PF survey corresponding to that given timepoint. Chi-square and Student t-test were used to compare demographic and perioperative variables between PROMIS respondents and nonrespondents. Student t-test for independent samples was used to compare scores for each of the other included PROMs between PROMIS respondents and nonrespondents at each timepoint. A p-value of ≤ 0.05 was set as the threshold for statistical significance for all tests.

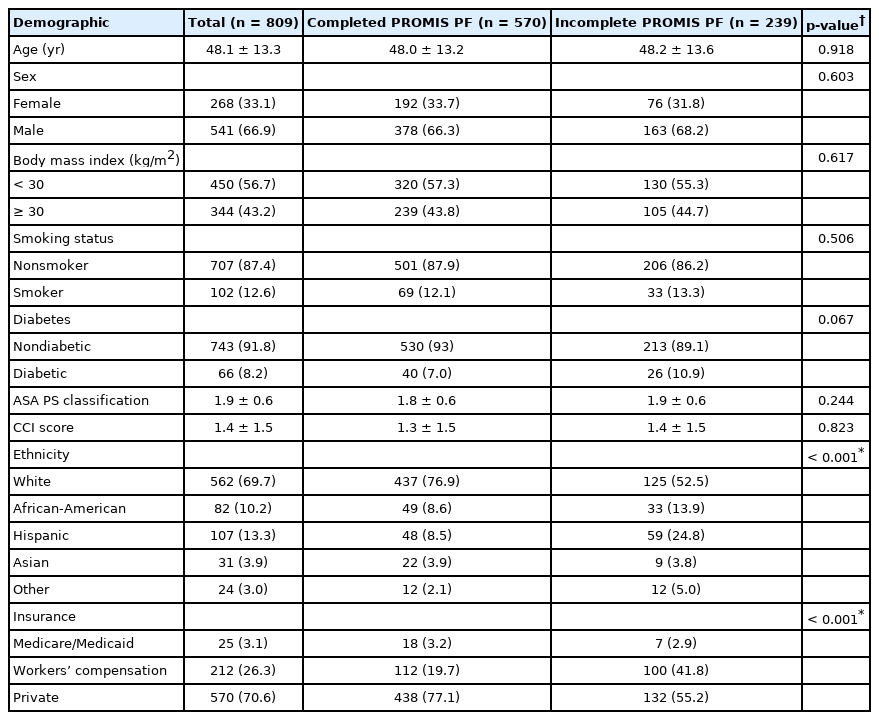

RESULTS

A total of 827 eligible lumbar spine patients were initially identified. Following removal of outliers, 809 patients were included in final analysis. The overall cohort had a mean age of 48.1 years and a majority were male (66.9%) and nonobese (BMI < 30 kg/m2; 56.7%). The mean ASA classification was 1.9 and mean CCI score was 1.4. Ethnicity (p < 0.001) and insurance/payment type (p < 0.001) were significantly associated with PROMIS completion status (Table 1). The study cohort included 335 lumbar fusion patients among whom degenerative spondylolisthesis was the most common preoperative spinal pathology (49.0%) and means for perioperative variables were as follows: operative duration 136.6 ± 45.8 minutes, EBL 52.1 ± 30.4 mL, and length of stay 32.7 ± 21.5 hours. The study cohort included 474 lumbar decompression/discectomy patients among whom herniated nucleus pulposus was the most common spinal pathology (82.7%) and means for perioperative variables were as follows: operative duration 46.0 ± 16.7 minutes, EBL 26.9 ± 9.2 mL, and length of stay 5.8 ± 7.6 hours. No perioperative variables significantly differed between PROMIS PF respondents and nonrespondents for either procedure type (Table 2).

No significant preoperative differences in any of the included PROMs were observed between PROMIS respondents and nonrespondents. PHQ-9 scores were significantly more severe for nonrespondents at 6 weeks (3.3 vs. 5.7, p < 0.001), 12 weeks (3.6 vs. 5.4, p = 0.005), 6 months (3.7 vs. 5.3, p = 0.007), and 1 year (4.0 vs. 5.7, p = 0.042). VAS back pain scores were significantly higher for nonrespondents at 6 weeks (3.1 vs. 3.8, p = 0.004), 12 weeks (3.2 vs. 4.1, p = 0.003), 6 months (3.3 vs. 4.3, p = 0.002), and 1 year (3.2 vs. 4.5, p = 0.004). VAS leg pain scores were significantly higher for nonrespondents at 6 weeks (2.8 vs. 3.6, p = 0.004), 12 weeks (2.8 vs. 3.4, p = 0.047), 6 months (2.8 vs. 3.7, p = 0.011), and 1 year (2.7 vs .3.9, p = 0.011). ODI scores indicated significantly more severe disability for nonrespondents at 6 weeks (27.6 vs. 35.0, p < 0.001), 12 weeks (25.2 vs. 33.9, p < 0.001), 6 months (24.1 vs. 323, p < 0.001), and 1 year (22.8 vs. 31.7, p = 0.009). SF-12 PCS scores were significantly poorer for nonrespondents at 6 weeks (35.9 vs. 32.5, p = 0.003), but not at any other timepoint (all p ≥ 0.090). A summary of postoperative PROM improvement by respondent group can be found in Table 3.

DISCUSSION

Defined as key differences in nonrespondents and respondents to a survey in a given population that may influence overall results, participation bias (also known as nonresponse bias) is a concern for clinical research, particularly those focused on PROMs. Such biases can be influenced both by the rate of response and the degree of difference between respondents and nonrespondents. Given that this bias is predicated on the absence of data, it is particularly difficult to quantify. Previous studies have utilized a variety of different methods to explore participation bias in surgical patients and report a wide range of results. Our analysis indicates significant differences in both the physical and mental health PROM scores of lumbar spine patients between respondents and nonrespondents to PROMIS PF surveys. These differences raise concerns for nonnegligible participation bias in the PROMIS scores of lumbar spine patients.

The challenging task of quantifying participation bias in PROs has necessitated a good deal of creativity on the part of researchers. One method employed by multiple orthopedic studies involves the use of a relatively generic, mail-based survey to categorize “respondents” and “nonrespondents,” followed by self-reported and more objective clinical data collection at subsequent follow-up appointments. Both Kwon et al. [13] and Kim et al. [14] conducted such analyses using a mail-based survey assessing satisfaction and functional status in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty.

Telephone-based outreach has also been utilized by several groups to connect with patients that did not respond to initial survey requests. In a study of patients from the Danish Shoulder Arthroplasty Registry, Polk et al. [15] utilized both postal reminders and telephone contact to increase completion rates of the Western Ontario Osteoarthritis of the Shoulder index from 65% to 82%. Højmark et al. [11] also studied nonrespondents to a mail-based survey from the Danish national spine database (DaneSpine) at 1 year follow-up by initiating contact through a structured telephone interview. Though this study is one of few to examine PROM participation bias in a cohort of spine patients, Cabitza et al. [9] also utilized telephone-based follow-up, but used a slightly less conventional method of characterizing and studying “nonrespondents.” These authors utilized phone-based reminders at 3 separate timepoints, and timed the third reminder such that patient responses had essentially ceased before this final outreach was attempted. Predicated on the idea that patients engaged by the third reminder otherwise would likely not have responded, outcome response data from these patients were used as a “proxy” for “true nonrespondents.”

Our group’s collection of a variety of different PROMs at multiple postoperative intervals allows us the opportunity to use data from “partial-respondents” who complete some PROMs but not others, to extrapolate potential trends for missing surveys. A number of previous studies have demonstrated robust correlations between PROMIS PF and the other physical healthrelated “legacy” PROMs utilized in our study. In their 2-year PROMIS validation study, Jenkins et al. [3] demonstrated strong correlations of PROMIS PF with VAS back, VAS leg, ODI, and SF-12 at both short- and long-term follow-up in patients undergoing transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. This finding has been similarly reproduced in other studies across a number of procedures including lumbar fusions and microdiscectomies [16-18], with the exception of Vaishnav et al, who reported a weak correlations of PROMIS PF with SF-12 preoperatively [19]. Based on these well-documented correlations, we can be confident that the completed PROM data we do have may provide useful information regarding the potential PROMIS scores for those that did not complete the PROMIS questionnaire. These relationships indicate that in cases where “legacy” PROM scores differ significantly between PROMIS respondents and nonrespondents, PROMIS scores may differ as well.

We identified 2 key demographic variables that were significantly associated with PROMIS completion. Specifically, the nonrespondent group included a larger proportion of patients who were African-American or Hispanic, and patients who made payments through workers’ compensation. Parrish et al. [5] previously examined demographic factors associated with PROMIS survey completion and reported similar trends of lower survey completion among African-American and Hispanic spine patients. While their study did not replicate our results regarding workers’ compensation patients, several investigations have reported poorer lumbar surgery outcomes among African-American and workers’ compensation populations [20,21]. These observed demographic variations in PROMIS response rates may contribute to and/or exacerbate the apparent response bias demonstrated in our results.

Although our analysis demonstrated substantial discrepancies in postoperative PROM scores, preoperative PROM scores did not significantly differ for any measure between PROMIS respondents and nonrespondents. This trend was demonstrated for both mental and physical health measures and may be particularly strong given that the greatest number of participants were included at these preoperative timepoints. Other studies of participation bias have reported similar results, with negligible preoperative differences between respondents and nonrespondents, even when significant differences emerged postoperatively [9,14]. One potential explanation for this observation is that differences in response rates may be influenced by patient experiences, perceptions, or outcomes of surgery. Perhaps patients hold relatively similar perceptions of surgery at the preoperative timepoint, given that they have all decided to pursue elective procedures, but these perceptions may diverge following varying postoperative outcomes and experiences. In fact, a number of studies have demonstrated that postoperative satisfaction is significantly associated with rates of survey completion [10,14].

In contrast with our preoperative results, PROMIS PF nonrespondents reported significantly worse back pain, leg pain, and disability at all postoperative timepoints. In their study of total knee arthroplasty patients, Kim et al. [14] demonstrated poorer mean scores and less postoperative improvement in pain, functionality, and Knee Society knee scores in patients that did not respond to their initial, mail-based survey. Cabitza et al. [9] also demonstrated poorer pain outcomes among survey nonrespondents in their cohort of hip, knee, and spine patients. However, others, such as Højmark et al. [11] and Kwon et al. [13] reported no significant difference in pain scores between respondents and nonrespondents.

PF, as measured by SF-12 PCS, demonstrated the least postoperative difference between PROMIS respondents and nonrespondents, with the nonresponding group demonstrating worse scores at the 6-week timepoint only. In previous validation studies, SF-12 PCS demonstrated some of the strongest, most consistent correlations with PROMIS PF [3,4]. Given that these measures are both specifically designed to assess physical functioning, the relative lack of difference in SF-12 PCS scores between PROMIS respondents and nonrespondents may be reassuring in terms of the validity of PROMIS data for drawing conclusions about the entire cohort. Our results conflict again with that of Kwon et al. [13] and also with Cabitza et al. [9] in this regard, as these studies both reported significantly poorer SF PF scores among survey nonrespondents.

In addition to the differences, we observed in physical health measures, patient-reported depressive symptoms, as measured by PHQ-9, were also significantly more severe at all postoperative timepoints for patients that did not complete PROMIS. Literature related to participation bias in measures of depression among surgical patients is quite limited. Cabitza et al. [9] was one of very few studies to include a measure of mental health status and, in contrast with their results regarding physical health, demonstrated no significant difference in SF mental component summary scores between respondents and nonrespondents. Several previous studies in more general medical populations have also reported minimal effects of participation bias with regard to depressive symptoms or mental health outcomes [22,23]. Nonetheless, the substantial differences we observed in depressive symptoms is concerning, especially considering evidence for a connection between PHQ-9 scores and physical outcomes in patients undergoing spine surgery [24-26].

The primary limitation of this study is that our use of legacy PROMs as a proxy for PROMIS scores did not allow us to study “complete nonrespondents” who did not complete any PROM surveys at all. These patients may differ from the 2 groups examined in our study in several important ways, and future studies of participation bias should consider alternative ways to capture outcomes in these patients. Additionally, all procedures in this study were performed by a single attending surgeon at the same academic institution. Therefore, the ability to generalize our results regarding PROMIS nonrespondents to other populations may be limited. A follow-up study using a multicenter design and an innovative method of engaging nonrespondents could be helpful to address these limitations. However, the current study provides a novel analysis of PROM trends in patients that did not complete the PROMIS PF survey, and presents important data regarding the potential for participation bias in this measure among lumbar spine patients.

CONCLUSION

No significant preoperative differences were observed for any of the assessed PROM scores between PROMIS respondents and nonrespondents. PROMIS nonrespondents demonstrated significantly poorer postoperative back pain, leg pain, disability, and depressive symptoms than respondents through 1-year following surgery. PF, as quantified by SF-12 PCS, generally did not differ between respondents and nonrespondents. Our results indicate that some degree of nonresponse bias may exist for PROMIS surveys, leading to a potential underestimation of PF deficits in the overall lumbar spine cohort, particularly at short-term postoperative timepoints. Efforts should be taken whenever possible to maximize survey completion and the outcomes of nonrespondents should be considered alongside available survey data.

Notes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding/Support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author Contribution

Conceptualization: CL, EC, KS; Data curation: CL, EC, CJ, SM, CG, KS; Formal analysis: CL, EC, KS; Methodology: CL, EC, KS; Project administration: CL, EC, CJ, SM, CG, KS; Visualization: CL, EC, CJ, SM, CG, KS; Writing - original draft: CL, EC, CJ, KS; Writing - review & editing: CL, EC, CJ, SM, CG, KS