Effectiveness of the Laminoplasty in the Elderly Patients with Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy

Article information

Abstract

Objective

The purpose of this study is to evaluate clinical and radiological outcomes analysis of the laminoplasty in the elderly patients, and to compare with the non-elderly patients.

Methods

A retrospective study of the short term result in patients who had treated with the laminoplasty for cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM) was performed. From January 2008 to December 2012, total 62 patients were operated with single open-door technique because of CSM; 28 patients were the elderly and 34 patients were the non-elderly. We evaluated some factors including sex, symptom duration, estimated blood loss during operation, operation time, hospitalization day, complications, pre- and postoperative modified Japanese Orthopedic Association (mJOA) score, recovery rate of mJOA score, achieved mJOA score, mean cervical canal width and expansion ratio of antero-posterior diameter in order to identify difference between the two group. Clinical outcomes were calculated with the recovery rate of mJOA score at the time of one year after operation.

Results

Mean age were 71.9 in the elderly group and 52.9 in the non-elderly group. Although postoperative mJOA score in the elderly group was lower than that of the non-elderly group, achieved mJOA score was statistically same between the two groups. Other clinical and radiological outcomes were also statistically same.

Conclusion

We conclude that the laminoplasty also assures good clinical outcomes in the elderly patients with CSM, same as in the non-elderly group.

INTRODUCTION

CSM is a neurologic disorder which is caused by narrow spinal canal due to degenerative changes in the cervical spine. Degenerative changes include herniation of cervical intervertebral discs, ossification of vertebral ligaments, hypertrophic changes in the vertebral bodies or facet joints and so on5,14). CSM may presents various clinical symptoms such as gait disturbance, decreased motor functions, sensory changes of the trunk or limbs, and abnormal responses of the pathologic ref lexes. Owing to the natural course of this disease entity, surgical interventions have been considered in order to prevent the neurologic deterioration.

Nowadays, it is widely accepted that the laminoplasty can achieve satisfactory clinical results for CSM, and there are a lot of studies about satisfactory outcomes, surgical techniques and so on. However, efficacies of laminoplasty for the elderly patients with CSM were still controversial. Additionally, several authors have reported that the elderly patients can't recover adequately comparing with the non-elderly patients within the laminoplasty15,17,19).

The purpose of this study aimed to analyze clinical and radiological outcomes of the laminoplasty in the elderly patients and compare with that of the non-elderly patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Patient Series

This is a retrospective study of the short term result after the laminoplasty. From January 2008 to December 2012, 89 patients were treated with the laminoplasty. 27 patients with traumatic cervical myelopathy, cerebral palsy, previous cervical surgery and spinal cord infarction were excluded. Thus, total 62 patients with CSM were included in this study. This study was consisted of 44 men and 18 women; the mean age was 61.5 years (range, 37-84 years). All patients had typical symptoms such as gait disturbance, limb weakness, pathologic reflexes and numbness.

These patients were divided into the following 2 groups by age as the elderly group (≥65 years) and the non-elderly group (<65 years); 28 patients were the elderly and 34 patients were the non-elderly. All of these patients were followed up at least one year, and this study focused on the short term clinical and radiological outcomes. The characters of the both groups are summarized with Table 1.

2. Surgical Procedures

In this study, all patients were operated by single open-door laminoplasty with Hirabayashi's method9). The spinous processes and laminae were exposed as much as possible and the paraspinal muscles were preserved so far as possible. We also separated the posterior ligament complex of upper and lower margins of the lesion. Using a high-speed pneumatic drill, a trough was drilled down to the ligamentum flavum on the open-door side. We drilled all the way through the laminae and made a very thin remnant of laminae. This thin rim and associated ligament were then removed with a Kerrison punch. And then, a second trough was drilled on the hinge side. We took care of making a trough without cutting the whole depth of laminae of hinge side, keeping the width of the slot 3-4mm in the hinge side. The opening on the open side was then gently expanded, thus lifting the lamina off the spinal cord and expanding the canal. While operator gently expanded the opening with a Penfield dissector or Raney clip applier, an assistant carefully rotated the lamina toward the hinge side. The door were kept open by placing the anchors (Centerpiece™ plate fixation system, Medtronic, Minnesota, USA) and fasten the door to the lateral mass. And then a drainage tube was inserted and the paraverterbral muscles and the skin were closed layer by layer. All patients equipped the Philadelphia neck brace at least one month in order to stabilize the cervical vertebrae and the paraverterbral muscles.

3. Analysis of Clinical Outcomes

Severity of myelopathy was evaluated at the times of admission date as preoperatively and one year after operation as postoperatively with a scoring system proposed by the Benzel et al.'s modified Japanese Orthopaedic Association Scale for cervical myelopathy (mJOA score)3). The mJOA score quantifies neurological impairment by evaluating upper extremity motor dysfunction with a range of 0 to 5, lower extremity motor dysfunction with a range of 0 to 7, sensory disturbance with a range of 0 to 3, and sphincter dysfunction with a range of 0 to 3 (Table 2). The recovery rate (RR) of mJOA score was evaluated using a formula suggested by Hirabayashi et al.9), and achieved mJOA score was also evaluated (Table 3).

Other clinical outcomes such as estimated blood loss during operation, operation time, hospitalization day and postoperative complications were also assessed.

4. Analysis of Radiological Outcomes

All cases had been routinely examined at the admission date or preoperative work up period for the operation with cervical spine plain films, cervical computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Postoperative radiological examinations were also taken several times at our outpatient department, we set the images at the one year after operation as short term result.

Mean canal width of antero-posterior diameter was measured at operated levels with cervical plain films as average of pre- and postoperative numerical values. We calculated the expansion ratio with followed formula; [expansion ratio=(postoperative value-preoperative value)/preoperative value×100%] (Fig. 1).

Mean canal width of antero-posterior diameter was measured at operated levels with cervical plain films as average of data of pre- and post-operative numerical values.

All of radiological examination analysis was performed by independent observers with three times repeating in order to induce accuracy.

5. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis were performed using PASW stastistics 18.0 (SPSS Inc, Hong Kong) software. All values are expressed as the mean±standard deviation. The Mann-Whitney U test and chi-square distribution test were performed for analyzing the differences between two groups. The p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

9 patients had double segments with the location being (C3-C5) in 6 cases and (C4-C6) in 2 cases and (C5-C7) in 1 case. 28 patients had triple segments with the location being (C2-C5) in 2 cases (C3-C6) in 21 cases and (C4-C7) in 5 cases. 25 patients had quadruple or more segments with the location being (C2-C6) in 5 cases and (C2-C7) in 7 cases and (C3-C7) in 13 cases.

The mean symptom duration was 9.5 months (range, 1-50 months). The mean preoperative modified JOA score was 12.2±2.2 (range, 7-16) and the mean postoperative modified JOA score was 15.3±1.3 (range, 12-17). The mean modified JOA recovery rate (RR) was 53.6±15.3%(range, 20.0-81.8%). The mean achieved modified JOA score was 3.11±1.6 (range, 1-9). The mean preoperative cervical canal width of antero-posterior diameter was 14.3±1.8mm(range, 10.1-18.6mm) and the mean postoperative cervical canal width of antero-posterior diameter was 20.2±1.8mm(range, 16.2-25.0mm). The mean cervical canal expansion ratio was 42.9±10.9% (range, 20.4-72.0%).

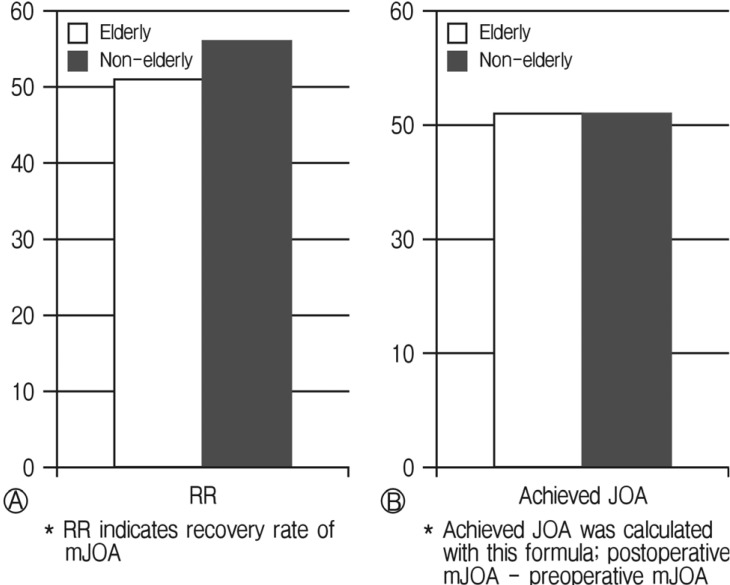

The mean symptom duration were 10.1±12.4 months in the elderly patients and 9.1±11.2 months in the non-elderly patients. The mean preoperative modified JOA score were 11.8±2.2 in the elderly patients and 12.6±2.1 in the non-elderly patients. The mean postoperative modified JOA score were 14.9±1.5 in the elderly patients and 15.7±1.0 in the non-elderly patients. In this study, the elderly patients group showed lower mJOA recovery rate and significantly lower postoperative mJOA scores (p<0.05) than the non-elderly group. However, there was no statistical difference of mJOA recovery rate between the elderly group and the non-elderly group. The mean mJOA recovery rate (RR) were 50.7±15.1% in the elderly patients and 55.9±14.8 in the non-elderly patients. Furthermore, the mean achieved mJOA score were statistically same between the two groups (Fig. 2, 3). The mean achieved mJOA score were 3.1±1.3 in the elderly patients and 3.1±1.8 in the non-elderly patients.

Pre- and postoperative modified JOA score in the both groups. Pre- and postoperative modified JOA score of the elderly group tend to show lower numerical values than those of the non-elderly group. Moreover, postoperative modified JOA score has statistical difference between the both groups (p<0.05).

Recovery rate of mJOA (A) and achieved JOA score (B) are statistically same in both groups (p>0.05). In this study, we cautiously conclude that the elderly patients can recover as well as the non-elderly patients.

In radiologic outcomes, the mean preoperative cervical canal width of antero-posterior diameter were 14.3±1.9mm in the elderly patients and 14.2±1.7 in the non-elderly patients. The mean postoperative cervical canal width of antero-posterior diameter were 20.4±2.0mm in the elderly patients and 20.1±1.6 in the non-elderly patients. The mean cervical canal expansion ratio were 43.4±11.0% in the elderly patients and 42.4±10.9% in the non-elderly patients.

There were postoperative infection of 2 cases, delirium of 1 case and C5 palsy of 1 case happened in the elderly group while postoperative infection of 1 case and hematoma collection in operation site of 1 case occurred in the non-elderly group. Although more complication cases were reported in the elderly group, it didn't have any significant distinction between the two groups. Estimated blood loss, operation time and hospitalization day were also statistically same in this study.

DISCUSSION

Since Hirabayashi et al. reported the cervical open-door laminoplasty for CSM in 198310), there were some studies which announced for comparisons of clinical outcomes between the elderly group and the non-elderly group those who had underwent cervical decompression for CSM in Japan8,14,15,16,17,19,21). Some authors divided patients into two groups as non-elderly and elderly, and another authors divided patients into three groups or more. However, their conclusions were still controversial, whether being divided into two or three groups is not the point. Like our study, some authors found no significant difference in JOA recovery rates between different age group, on the contrary, others reported that JOA recovery rates tended to decrease with aging. Latter authors supposed that age-related changes in the spinal cord might explain the reasons why the elderly patients usually don't recover adequately after lamoniplasty those in the non-elderly patients15,16). However, all authors identified that cervical decompression has enough effectiveness for the elderly patients with CSM.

In case of Japan, some authors had concluded that patient age influences on the clinical outcome of the laminoplasty5,22). In this study, although preoperative modified JOA score was statistically same between the elderly group and the non-elderly group, postoperative modified JOA score was different between the two groups. However, modified JOA recovery rate and achieved modified JOA score were statistically same. Clinical outcomes such as modified JOA recovery rate or achieved modified JOA score in the elderly group were comparable with those in the non-elderly group. According to this result, the laminoplasty for CSM was also effective in the elderly patients. Thus, if the patient is in good physical condition, old age alone is not a contraindication to this surgical treatment for CSM. Yoon et al. had reviewed 433 previous citations which had designed a systematic-review to evaluate potential predictive factors of the laminoplasty for CSM23). 12 studies of them were related to age which is predictive factors affecting outcome after the laminoplasty. Like our study, authors also found out that increased age is not a strong predictor of clinical outcomes after the laminoplasty, therefore age by itself should not preclude the laminoplasty for CSM.

Meanwhile, JOA recovery rate is a simple and useful parameter to compare clinical outcomes quantitatively. However, the usage of this score may be unreasonable. As JOA recovery rate can be alterable due to preoperative JOA score even if the same achieved JOA score were taken. Machino et al. announced a large-scale study of the surgical outcome for CSM from a single operative procedure with double-door laminoplasty in 520 elderly patients14). They pointed out that actual surgical outcome in patients with the same recovery rate may differ due to the preoperative JOA scores. For example, if someone gets same point of achieved JOA score after operation, recovery rate is changed due to the preoperative JOA score. Therefore, they concluded that surgeons should consider JOA recovery rate as well as achieved JOA score in order to evaluate clinical outcomes appropriately.

In the aspect of measuring for assessment of CSM, Kalsi-Ryan et al. had reviewed related articles for identifying the most suitable measurement of the scoring systems for CSM13). The goal of their review was to establish the most reliable, valid, responsive, sensitive and quantitative measurement of CSM. Their review was consisted of 3 steps. First step, they defined the measurements which are currently used in the literatures. In their review, Nurick scale18), modified JOA scale3), visual analogue scale (VAS) for pain, Short-form 36 health survey (SF-36)7), neck disability index (NDI)1), the myelopathy disability index (MDI)6) and european myelopathy scale (EMS) were in order of citation times. They also analyzed validity, reliability and responsiveness of these measurements. Second step, they pointed out that these measurements don't objectively quantify the physical findings of the individual. And they made the criteria which are consist of six outcome measurements in terms of ancillary measurements. QuickDASH2,11), Berg balance scale4), 30-meter walk test (30MWT)20), graded redefined assessment of strength sensibility and prehension (GRASSP)12), grip strength (dynamometer) and GAITRite analysis (computerized walkway system) were included in their criteria. Third step, they focused on the literature about these ancillary measurements, and they also introduce that how these ancillary measurements can be useful in clinical practices. In conclusion, they recognized that it can't define with a single score on a single outcome measurement for CSM because of its heterogeneity. Thus, they suggested that clinician can obtain more reliable, valid, responsive and quantitative information in the CSM population using these ancillary measurements.

Our study has several limitations. First, it is often difficult for the elderly patients to assess their neurological functions exactly because some of them don't have enough communicative competence to express their symptoms. Secondly, this study may contain a selection bias. If a patient have serious comorbidity, surgeons can't operate them or anesthesiologists refuse to anesthetize that patient. And most patients with CSM were considered for operation, so an adequate number of control groups who had underwent conservative therapy could not be obtained. Thirdly, we set up one year follow up as the point of times for evaluating clinical outcomes. However, these data are just short-term follow up data, so there is a possibility that these data don't reflect on the natural course of postoperative recovery. Therefore, it is necessary that long-term follow up or final follow up analysis should be reinforced for further work-up.

CONCLUSION

In the present study, the elderly patients treated with laminoplasty for CSM showed favorable clinical and radiological outcomes, same as the non-elderly patients. Additionally, incidence of postoperative complications was not significantly increased.

We conclude that the laminoplasty for the elderly patients with CSM assures satisfactory clinical and radiological results.