Spontaneous Spinal Subdural Hematoma causing Brown-Séquard Syndrome with Thrombocytopenic Myelodysplastic Syndrome

Article information

Abstract

Spontaneous spinal subdural hematoma (SSDH) is a very rare condition. We report a case of SSDH presenting with Brown-Séquard syndrome, treated by surgical evacuation. A 77-year-old woman was hospitalized for back pain without trauma history. As she showed progressive sensory loss and right-side dominant paraparesis, we performed magnetic resonance imaging and confirmed the SSDH in the thoracic area. Therefore, she underwent emergent operation and the hematoma was evacuated successfully. After the operation, the patient showed improvement in neurologic function.

INTRODUCTION

Spinal subdural hematoma (SSDH) is an uncommon lesion, and spontaneous, non-traumatic hematoma formation in the spinal subdural space is very rare. Only 21 spontaneous SSDH cases have been reported until now913). SSDH should be considered an emergency and diagnosed and treated accordingly for efficient management before irreversible neurological deterioration2).

SSDH is clinically characterized by back pain, spreading to upper or lower extremities or to the trunk, with variable degrees of progressive motor and sensory deficits8). The treatment of choice for SSDH with neurologic impairment is immediate evacuation of the hematoma or hemorrhage7).

We report a case of spontaneous thoracic subdural hematoma presenting with Brown-Séquard syndrome, which was treated by surgical evacuation.

CASE REPORT

A 77-year-old woman experienced thoracic back pain for 2 days, and received emergency hospitalization for gradual gait disturbance and numbness in both legs. Two days before the hospital visit, she experienced upper thoracic back pain without motor weakness. There was no specific trauma history. She had no history of medication with antiplatelet or anti coagulant agents, and was incidentally diagnosed with thrombocytopenia 2 years ago. The thrombocytopenia was not evaluated or treated upon her request.

Initially, the patient assumed it to be a back sprain. However, with time, the severity of pain increased, and spread across the localized inter-scapular area to most of the back area despite analgesic medications.

Her initial symptoms were back pain and weakness in both legs, and neurologic examination revealed the motor strength to be 4-/5 in all the muscle groups of the right lower extremity, and 4/5 in all the muscle groups of the left lower extremity. Sensory modalities were normal, including sensations of pain, temperature, joint position, and vibration in the feet and perineal region. Deep tendon reflexes were mildly hyper-reflexed. Anal sphincter and bulbocavernosus reflexes were intact.

However, laboratory data showed coagulopathy, including delayed activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) (aPTT 44.9 sec, normal range <35 sec), and thrombocytopenia (platelet count: 42,000/mm3 [normal range: 154,000-350,000]). The hemoglobin level was 13.3 g/L, international normalized ratio (INR) was 1.23, prothrombin (PT) was 15.5 sec, and other laboratory data were normal.

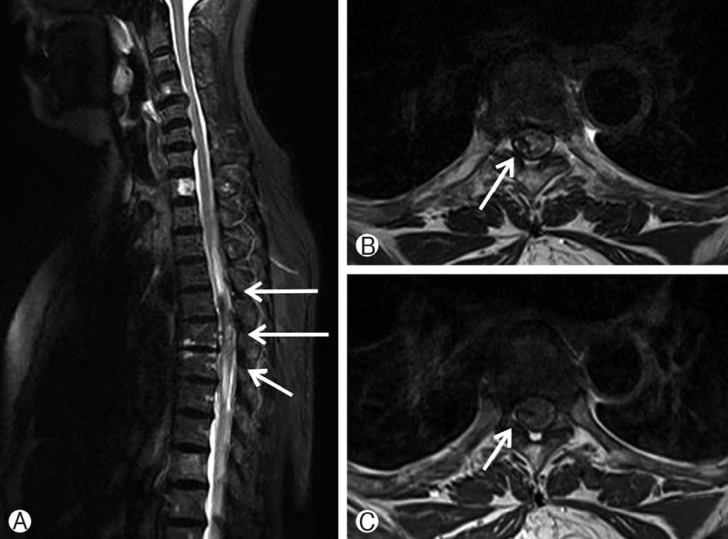

Enhanced spinal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the cervico-thoracic region was performed. The MRI findings showed that the lesion was hyperintense on T2-weighted and isointense on T1-weighted images, and located in the right portion of the spinal cord longitudinal from T5 to T7 with significant leftward compression of the spinal cord accompanying peripheral edema from T3 to T8 (Fig. 1). On an enhanced T1-weighted image, a heterogeneous weakly enhanced portion was found. Initially, the patient had only back pain and minimal neurologic deficit; therefore, we decided to further observe and differentiate the lesion from tumor, vascular malformation, and hematoma.

Initial Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the thoracic spine demonstrated a well-defined mass in the subdural space extending longitudinally from the level of T5 to T7 level causing significant compression of spinal cord with maximum compression at the level of T6 with extended edematous change in the cord (A). The lesion is hypointense on T2-weighted image, compre ssing spinal cord (B), and heterogeneously weakly enhanced lateral subdural lesion was found (C).

Paraparesis in both legs was insignificant initially; however, a day after admission, neurologic deterioration occurred with a motor strength of 1/5 in all the muscle groups of the right lower extremity, and 3/5 in all the muscle groups of the left lower extremity. Below the 10th thoracic dermatome level, pain and temperature perception on the left side decreased by about 30% compared with the right side. Her sense of touch, vibration, and proprioception on the right side were decreased. The patient had spasticity with hyper-reflexia in both legs, and a positive Babinski reflex on the right side. The bulbocavernosus reflex was positive and anal tone decreased.

We immediately performed a follow-up MRI. The MRI showed an increasing mass lesion and edema at the cord that spread from the C7 to T9 level (Fig. 2). Finally, we diagnosed this lesion as progressing SSDH.

Follow up MRI in 14 hours after initial symptom onset showed growth of mass lesion in T4 to T7 level with increased edema in the cord from C7 to T9 level (A). The lesion is at posterolateral portion with low signal intensity on T2-weighted image (B), T1-weighted image showed iso-signal intensity (C), compressing spinal cord.

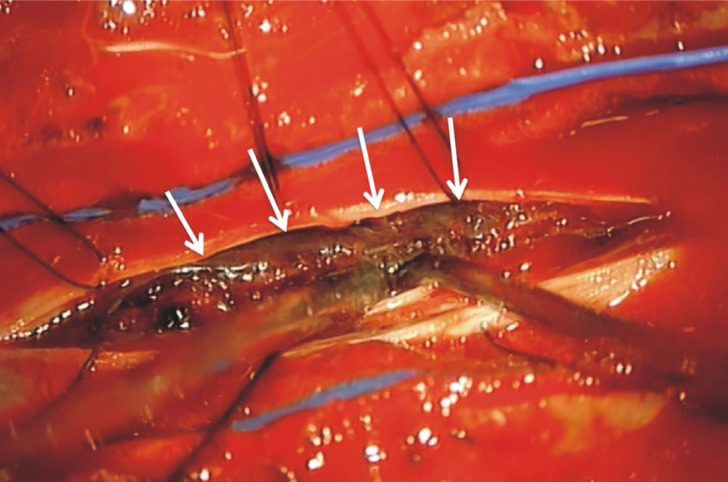

We performed an emergent decompressive surgery with T5-6 laminectomy after platelet transfusion. Intra-operatively, the dural sac was tense; a subdural extramedullary thick blood clot and prominent subdural vessels were found without vascular malformation, and confirmed by microscopic inspection (Fig. 3). The organized portion of the hematoma adherent to the spinal cord was almost totally removed. After the hematoma evacuation, the cord was adequately decompressed.

Hematoma in the subdural space in operative view. The arrows indicate intradural hematoma that compressing the cord.

Postoperatively, her immediate neurological status was the same as that preoperatively. However, the patient's sensory function recovered and motor function gradually improved to a motor strength of 3/5 in both lower limbs. Thirty days postoperatively, she regained 80% of her preoperative hypoesthesia including pain perception. She had minimal spasticity in both lower legs, but did not show bladder or bowel control problems.

After rehabilitation, the patient underwent bone marrow biopsy, and was diagnosed with thrombocytopenia in suspected myelodysplastic syndrome, specifically, refractory cytopenia with unilineage dysplasia. She underwent periodic outpatient follow-up checks. After 6 months, paresis in both the legs as well as hypoesthesia below the 10th thoracic level persisted.

DISCUSSION

Spontaneous SSDH without underlying pathologic causes, such as tumors or ruptured vascular malformations including arteriovenous malformations (AVM), or aneurysms of the spinal arteries, is extremely rare2). Spontaneous SSDH occurs most often in the thoracic spine and manifests as sudden back pain that radiates to the upper or lower extremities78).

Moreover, multifarious neurologic deficits are presented, from mild motor or sensory abnormalities to severe weakness or bladder dysfunction9). In this case, initial neurologic deficit was mild; however, neurologic deterioration occurred in short time including sensory dissociation and right side dominant weakness, suggesting Brown-Séquard syndrome.

Several studies have reported spontaneous SSDHs after anticoagulant therapy; spontaneous cranial subdural hematoma could occur from thrombocytopenic conditions such as thrombocytopenic purpura, HIV infection, and systemic lupus erythematosus111215). However, this is the first report of a patient with a spontaneous SSDH clinically presenting with Brown-Séquard syndrome, and diagnosis of thrombocytopenia.

Brown-Séquard syndrome clinically manifests as a complete loss of ipsilateral light touch sensation and proprioception, loss of contralateral pain and temperature sensation, and ipsilateral motor paralysis. Most patients, however, experience an incomplete Brown-Séquard syndrome with only partial sensory and motor impairment like our patient.

The neurologic interruption is caused mainly by unilateral involvement of the lateral corticospinal tract, dorsal column, and ventral spinothalamic tract of the spinal cord15). In our patient, Brown-Séquard syndrome was an expected result of SSDH as anatomically illustrated by MRI. It resulted from a serially increasing subdural hematoma compressing the spinal cord leftward. Progression of ipsilateral leg weakness and loss of ipsilateral tactile, vibratory, and position sensation, and contralateral pain and temperature sensation below the level of 10th thoracic dermatome were the clinical features of Brown-Séquard syndrome in our case.

In Korea, three cases of spontaneous SSDH presenting with paraparesis have been previously reported-two cases affecting the ventral portion and one case with a dorsal hemorrhage13). All three underwent lumbar drainage and methylprednisolone pulse therapy617), with good clinical outcome. According to Boukobza et al.1), conservative treatment is possible if early recovery is observed, deficits are mild, degree of hematoma extension precludes surgical treatment, or a coagulopathy is associated. In the present case, the patient went through progressive aggravation of neurologic status even though coagulopathy existed; therefore, the treatment included emergent decompressive laminectomy and evacuation of the hematoma to prevent or minimize permanent neurological damage caused by spinal cord compression, ischemia, and/or spinal cord injury2). The patient underwent emergent decompressive surgery with platelet transfusion to counteract the low platelet condition.

This unusual presentation can be confused with a cerebrovascular accident, which can lead to delayed or misdiagnosis. Because the patient's neurologic feature reflected a spinal lesion more, we did not take any brain evaluation. Careful neurologic examinations are very important to decision to study as a course of appropriate treatment.

Several studies have reported that acute spinal subdural hematoma can occur from spinal vascular malformation, aneurysm or spinal cord angioma with very low incidence41018). Langmayr et al.10) reported a case of SSDH caused by spinal aneurysm rupture from radicular artery in 8th thoracic level. Pia found 38% of intradural angiomas were associated with spinal hemorrhage including subdural hematoma, subarachnoid hemorrhage and hematomyelia on his study14). And also, according to Defreyne et al.3), venous outflow restriction and/or venous thrombosis can cause rupture of AVM, which induce spinal hemorrhage including subdural hematoma. Therefore angiography should be performed to rule out vascular diseases before the operation because angiography is the best modality for identifying arteriovenous fistula, AVM, or aneurysm. However in our case, due to the rapidly progressing weakness in both legs, decompressive laminectomy and hematoma evacuation were performed. And it finally resulted in no evidence of vascular malformations in the hematoma in intraoperative view.

The prognosis is variable and the precipitating factors are still speculative. Thiex et al.19) reported the functional outcome of spontaneous and nonspontaneous SSDH after surgical treatment. The outcome was determined by the preoperative sensorimotor function and spinal level of SSDH. A previous study stressed that the early correction of coagulopathy and a prompt and non-invasive diagnosis by spinal MRI leads to efficient surgical treatment16). According to Kyriakides et al.9), patients usually demonstrate slow but good neurologic recovery regardless of the treatment method, and intensive rehabilitation programs, including physiotherapy and bladder and bowel management, are vital to ensure good recovery.

CONCLUSION

Spontaneous SSDH is a relatively uncommon lesion, and is a previously undocumented cause of Brown-Séquard syndrome. Sudden onset of back pain with paraparesis and with or without focal neurological deficits should be assessed with contrast-enhanced MRI. It must be noted that SSDH can clinically present as Brown-Séquard syndrome. Careful examinations and appropriate evaluation should be performed to avoid postponing treatment. If neurological deterioration occurs, emergency decompressive surgery should be performed.