|

|

- Search

Abstract

Objective

Cervical spondylosis and shoulder disorders share with neck and shoulder pain. Differentiating between the two can be challenging and patient with combined pathologies is less likely to have pain improvement even after successful cervical operation. We investigated clinical characteristics of the patients who were diagnosed as cervical spondylosis however, were turned out to have shoulder disorders or the patients whose pain was solely originated from shoulder.

Methods

Between January 2008 and October 2009, the patients presenting neck and shoulder pain with diagnosis of cervical spondylosis were enrolled. Among them, the patients who met following inclusion criteria were grouped into shoulder disorder group and the others were into cervical spondylosis group. Inclusion criteria were as follows. (1) To have residual or unresponsive neck and shoulder pain despite of optimal surgical treatment due to concomitant shoulder disorders. (2) When the operation was cancelled for the reason that shoulder and neck pain was proved to be related with unrecognized shoulder disorders. The authors retrospectively reviewed and compared clinical characteristics, level of pathology, diagnosis of cervical spondylosis and shoulder disorders.

Results

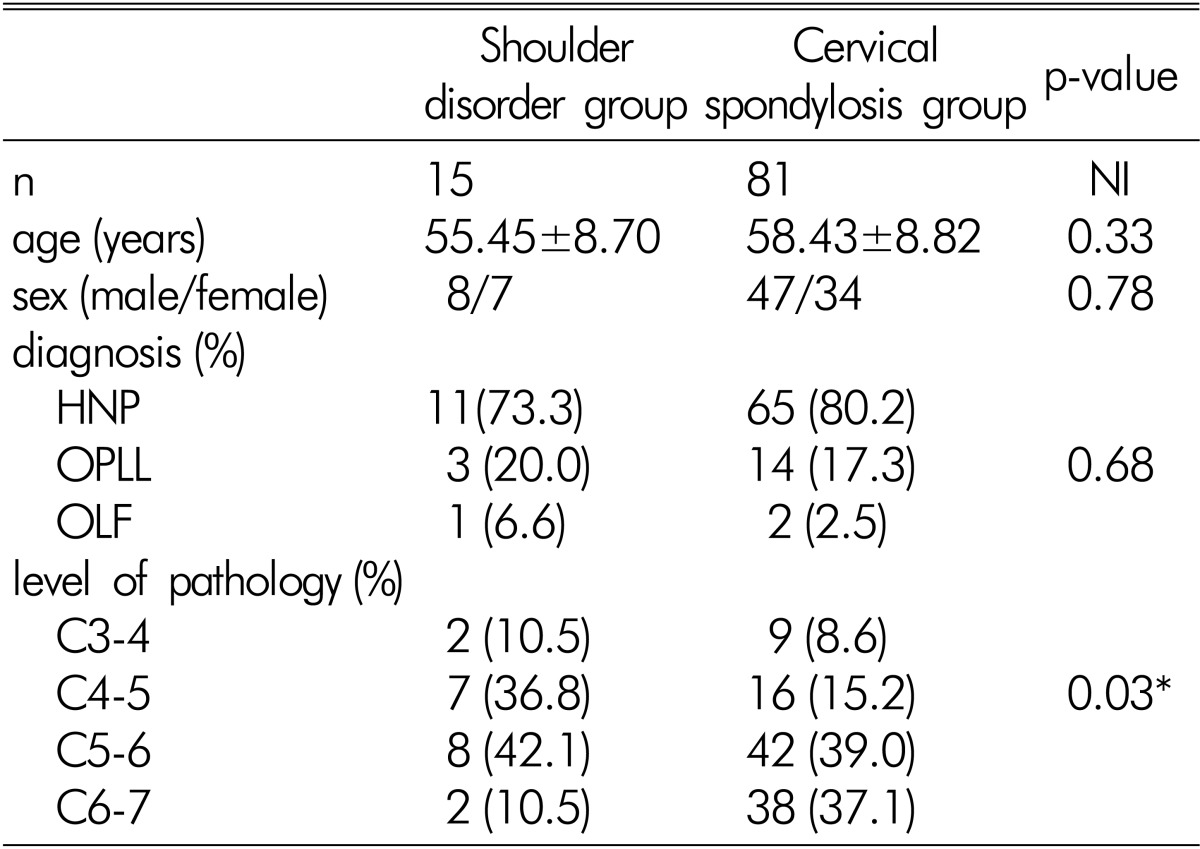

A total of 96 patients were enrolled in this study. Shoulder disorder group was composed of 15 patients (15.8%) and needed additional orthopedic treatment. Cervical spondylosis group was composed of 81 patients (84.2%). There was no significant differences in mean age, sex ratio and major diagnosis in both shoulder disorder and cervical spondylosis group (p=0.33, 0.78, and 0.68 respectively). However, the distribution of pathologic levels was found to be significantly different (p=0.03). In shoulder disorder group, the majority of lesions (15 of 19 levels, 78.9%) were located at the level of C4-5 (36.8%) and C5-6 (42.1%). On the other hand, in cervical spondylosis group, C5-6 (39.0%) and C6-7 (37.1%) were the most frequently observed level of lesions (80 of 105 levels, 16.1%).

Pain of the neck and shoulder are common complaints in the primary care setting. Neck pain is the second most common reason for visit to hospital and the following is shoulder pain, which is accounting for approximately 5% of visit to primary care offices3,11). As two types of pain often present with same symptoms, differentiating between the two can be demanding and challenging.

Cervical spondylosis refers to age-related degenerative changes within cervical spine and entails a variety of clinical manifestations including neck pain, cervical radiculopathy and myelopathy. These symptoms could be surgically indicated if they are medically intractable, accompanying neurologic deficit and confirmed by image studies as well. However in the setting of combined dual pathologies from both cervical spondylosis and shoulder disorders, even after the successful operation was done, patient could not be guaranteed a complete relief of pain or functional recovery in daily life. Thus, spine surgeons should be aware of that pain in the neck and shoulder might signal lesions that are not intrinsic to cervical spondy losis.

The author in present study investigated clinical characteristics of the patients presenting neck and shoulder pain who were diagnosed as cervical spondylosis in the first place however, were turned out to have shoulder disorders simultaneously or the patients whose pain was solely originated from shoulder. In addition, we also introduced several kinds of physical examinations for differentiating between cervical spondylosis and shoulder disorders.

Authors retrospectively consecutively reviewed patients who visited out-patient clinic with complaint of neck and shoulder pain and diagnosed as cervical spondylosis between January 2008 and October 2009. Diagnosis was made based on image findings, medical history and physical examination. Among these patients, the patients who fell into one of next inclusion criteria were enrolled in shoulder disorder group (case group) and the rests were enrolled in cervical spondylosis group (control group). The inclusion criteria of shoulder disorder group were as follows. (1) To have residual or unresponsive neck and shoulder pain despite of optimal surgical treatment due to concomitant shoulder disorders that needs additional orthopedic treatment. (2) When the operation was cancelled for the reason that shoulder and neck pain was proved to be related with unrecognized shoulder disorders.

We collected the patients' demographic information and assessed specific type of cervical spondylosis including degenerative cervical HNP (herniated nucleus pulposus), OPLL (ossified posterior longitudinal ligament) and OLF (ossified ligamentum flavum). Distribution of pathologic level of degenerative cervical spine disease was also assessed and analyzed using Picture Archiving and Communication Systems (PACS) terminal (Marosis 2003, Seoul, Korea). In the cases that unrecognized shoulder disorders was dominant pathology to neck and shoulder pain, medical records containing the history of orthopedic treatment were reviewed and its specific diagnosis was figured out.

For comparisons of categorical variables, Fisher's exact test was used and continuous variables were compared either using student's t-test after verification of normal distribution by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test or using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test. A p value less than 0.05 was regarded to be statistically significant.

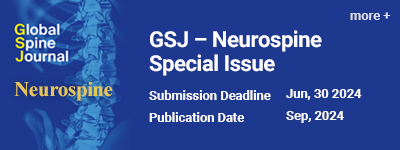

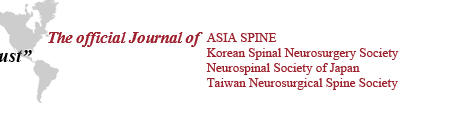

Additionally, the authors reviewed several physical examinations that were believed to be helpful in differentiating and diagnosing of shoulder disorders and cervical spondylosis. These are as follows. The Neer's test (Fig. 1A), the Hawkins' test (Fig. 1B), and the Jobe's test (supras- pinatus test, Fig. 1C) were for shoulder disorders, Spurling's test (Fig. 2A) and the Bakody's test (shoulder abduction release test, Fig. 2B) were for cervical spondylosis.

A total of 96 patients who had neck and shoulder pain were diagnosed as degenerative cervical disease and optimal surgical treatment was indicated. Shoulder disorder group was composed of 15 patients (15.8%). Of these patients, 12 patients (12.5%) experienced unsatisfied pain relief after cervical spine surgery and in 3 patients (3.1%), planned operation was cancelled because it was revealed that neck and shoulder pain was truly originated from shoulder, not from cervical spine. Shoulder disorders were distributed as 4 cases of frozen shoulder (26.6%), 4 cases of rotator cuff tear (26.6%), 3 cases of adhesive capsulitis (20.0%), 2 cases of tendon impingement (13.3%), 1 case of calcific tendinitis (6.6%) and 1 case of shoulder joint subluxation (6.6%). All these patients were referred to orthopedic department and during the follow up periods, the patients' pain had improved considerably.

Cervical spondylosis group was composed of 81 patients (84.2%) and Table 1 shows the comparison between two groups. The mean age of shoulder disorder and cervical spondylosis group was similar (p=0.33) each other, and there was no significant difference in sex ratio (p=0.78) as well. HNP was a major diagnosis of both shoulder disorder (73.3%) and cervical spondylosis (80.2%) group and the following was OPLL (20.0%, 17.3%, respectively) in both groups. The composition ratio of diagnosis in shoulder disorder group was not significantly different with that of cervical spondylosis group (p=0.68). Howe ver, the distribution of pathologic levels was found to be significantly different (p=0.03) between two groups. In shoulder disorder group, the majority of lesions (15 of 19 levels, 78.9%) were located at the level of C4-5 (36.8%) and C5-6 (42.1%). On the other hand, in cervical spondylosis group, C5-6 (39.0%) and C6-7 (37.1%) were the most frequently observed level of lesions (80 of 105 levels, 76.1%).

Pain experienced in the shoulder, upper, and lower arm can be as a result of a various medical conditions10), including mechanical pain from nearby musculoskeletal structures such as the shoulder or the cervical spine13). Unfortunately, differentiating between neck and shoulder pain can be challenging as both share symptoms and the clinical presentations of cervical spondylosis and shoulder disorders are similar4). In current study, it was revealed that 15 patients (15.8%) who had been diagnosed as cervical spondylosis had underlying, unrecognized shoulder disorders. Among those 15 patients, 3 patients (3.1%) were misdiagnosed and came close to doing unnecessary cervical operation instead of orthopedic shoulder treatment. As far as we know, there has been no report mentioning specific rate regarding misdiagnosis or undetected shoulder disorders when attempting to do a cervical operation. Although direct comparison with any other literature is not possible, it is considerably higher than our expectation.

In present study, it was found that most lesions (70%) in cervical spondylosis group were located at the level of C5-6 level, followed closely by C6-7 level and this result was coincident with that of Gore et al.5)'s study. In shoulder disorder group, however, the majority of shoulder disorder group (78.9%) had concurrent cervical pathologies at the level of C4-5, C5-6 and accordingly, C5 and C6 nerve root irritation symptom was most frequently observed clinical presentation. The cervical nerve roots at the C5 through C6 levels combine to form the upper, middle, and lower trunk in brachial plexus. These trunks are separated into two divisions: the anterior and posterior. These divisions reunite to form the lateral, posterior, and medial cords. The posterior cords are the base of two nerves that innervate the neuromusculature of the shoulder stabilizers. The upper subscapular nerve innervates the subscapularis muscle. The lower subscapular nerve also provides a branch to the subscapularis. The axillary nerve provides sensation to the skin over the lower deltoid as well as motor function to the entire deltoid. Radiculopathy arising from C5 and C6 is very difficult to differentiate from shoulder pathology because the sensory distribution runs from the base of the neck to the outer edge of the shoulder14). Radiculopathy of any of the cervical nerves 4 to 6 can produce pain in the scapula, shoulder, upper arm, lower arm and hand. The muscle of the deltoid is innervated by the C5 nerve root and can present as acute rotator cuff pathology. Cervical radiculopathy primary presents with motor and sensory symptoms on the affected limb, and acute symptoms generally result from cervical disk herniation8). We assumed that the agreement between frequently involved C5 and 6 nerve roots in shoulder disorder group and its anatomical role in the genesis of shoulder pain might make spine surgeons difficult to find underlying shoulder disorders and this could leads to high rates of misdiagnosis or fail of recognition in our series.

To make the differential diagnosis accurate and easier, appropriate questioning during the history and selected physical examination will be needed. The exam includes special tests that are considered the hallmarks of specific symptoms. These tests include the Neer's, Hawkins' and Jobe's tests for rotator cuff pathology. The tests for cervical involvement use the dermatomal chart and the Spurling's and Bakody's tests4,14).

The Neer's test (Fig. 1A) is used for impingement of the rotator cuff tendon. The examiner prevents the scapular from moving and places hand on the patient's forearm to force resistance against further forward flexion. Pain in the anterior portion of shoulder due to impingement of the greater tuberosity against acromion is regarded positive 9).

The Hawkins' test (Fig. 1B) was described as alternative to the Neer's test6). The patient forward-flexes the arm to 90 degrees and flexes the elbow to 90 degrees. The examiner then internally rotates the humerus with force to try to impinge the greater tuberosity against the acromion.

The Jobe's test (Fig. 1C) also known as supraspinatus test is for supraspinatus tendon which is most commonly injured owing to its orientation to the anterior acromion7). The patient abducts the arm to 90 degrees, and from there the arm is angled forward 30 degrees. The examiner places his hand on top of the arm to provide resistance while the patient tries to lift against the resistance. When there is pain along the superior lateral deltoid muscle with muscle weakness, it is regarded as positive test.

Among these tests, the Neer's and the Hawkins' tests have a merit that they are suitable during the screening process as both tests have high sensitivity. Calis et al1) reported sensitivity of the Neer's test at 89% and of the Hawkins' test at 92%.

There are several kinds of special tests for disorders of cervical spine. The Spurling's test (Fig. 2A) is used for its effectiveness in diagnosing cervical radiculopathy. The patient extends the neck and laterally tilts the head to the affected side. This position narrowed the neural foramen and will recreate the pain of the affected shoulder. Although this test is less sensitive (average 30%), it was known to be highly specific (average 93%)12).

The Bakody's test2) (Fig. 2B), also known as shoulder abduction release test, is also used for diagnosing cervical spine disorders. This test examines C4 and 5 root. With raising the affected arm over the head so that the hand rests on top of it, symptoms in this position indicate extradural compression lesion such as herniated disk.

Above mentioned tests give us the information how a patient with diffuse complaints of neck and shoulder pain may actually have either shoulder pathology or cervical pathology. And we believe if these tests could be performed correctly, the chief complaint can be narrowed down to either shoulder or cervical disorders.

Differentiating among the causes of neck and shoulder pain can be difficult and demanding, as the clinical symptoms of cervical spondylosis and shoulder disorders are similar each other. In present study, most cervical lesions of shoulder disorder group occurred at the level of C4-5, C5-6 while most of pathologic lesions were observed at the level of C5-6, C6-7 in cervical spondylosis group. Because both C5, 6 roots are ana tomically responsible for sensory and motor function of shoulder, it is easy for spine surgeons to fail to detect unrecognized shoulder disorders in patient with neck and shoulder pain. Thus, to make a precise diagnosis, it is very important for spine surgeons to perform a complete history taking and physical examination using the above mentioned special tests, and to discover the underlying cause of the symptoms in treatment of cervical spondylosis presenting neck and shoulder pain.

References

1. Calis M, Akgun K, Birtane M, Karacan I, Calis H, Tuzun F. Diagnostic values of clinical diagnostic tests in subacromial impingement syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis 2000 59:44-47. PMID: 10627426.

2. Evans R. Illustrated essentials in orthopedic physical assessment. St. Louis: Mosby Year Book; 1994.

3. Ferrari R, Russell AS. Regional musculoskeletal conditions: neck pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2003 17:57-70. PMID: 12659821.

4. Fish DE, Gerstman BA, Lin V. Evaluation of the patient with neck versus shoulder pain. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2011 22:395-410. viiPMID: 21824582.

5. Gore DR, Sepic SB, Gardner GM, Murray MP. Neck pain: a long-term follow-up of 205 patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1987 12:1-5. PMID: 3576350.

6. Hawkins RJ, Kennedy JC. Impingement syndrome in athletes. Am J Sports Med 1980 8:151-158. PMID: 7377445.

7. Jobe FW, Jobe CM. Painful athletic injuries of the shoulder. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1983 117-124. PMID: 6825323.

8. Malanga GA. The diagnosis and treatment of cervical radiculopathy. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1997 29:S236-S245. PMID: 9247921.

9. Neer CS. Anterior acromioplasty for the chronic impingement syndrome in the shoulder. 1972. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005 87:1399PMID: 15930554.

10. Pateder DB, Berg JH, Thal R. Neck and shoulder pain: differentiating cervical spine pathology from shoulder pathology. J Surg Orthop Adv 2009 18:170-174. PMID: 19995495.

11. Stevenson JH, Trojian T. Evaluation of shoulder pain. J Fam Pract 2002 51:605-611. PMID: 12160496.

12. Tong HC, Haig AJ, Yamakawa K. The Spurling test and cervical radiculopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002 27:156-159. PMID: 11805661.

13. Tyler TF, Nicholas SJ, Lee SJ, Mullaney M, McHugh MP. Correction of posterior shoulder tightness is associated with symptom resolution in patients with internal impingement. Am J Sports Med 2010 38:114-119. PMID: 19966099.

14. Wilson C. Rotator cuff versus cervical spine: making the diagnosis. Nurse Pract 2005 30:44-46. 48-50. PMID: 15891620.