Sudden Onset of Cauda Equina Syndrome Resulting from Posterior Migration of Lumbar Herniated Disc Without Significant Previous Neurological Signs

Article information

Abstract

While extruded disc fragments are known to migrate anteriorly, posteriorly, or laterally to the theca sac, posterior migration of the fragments is relatively rare and sudden onset of cauda equina syndrome (CES) caused by the migration is extremely rare. The authors experienced a case of CES that was manifested abruptly with sudden paraplegia caused by posterior migration of the lumbar intervertebral disc. A 74-year old man, who had no prior significant neurologic signs or trauma history, visited our emergency center with paraplegia of both lower extremities occurring suddenly when awakened. On magnetic resonance image (MRI) findings, we could detect ruptured disc herniation with severe lumbar stenosis at the L2-3 level. We performed an emergent decompression, and the right posterior migrated disc fragments at L2-3 were intraoperatively observed. The patient was fully recovered himself on the follow up after 3 months of the operation. In conclusion, early operation can result in better outcome in acute paraplegia caused by the posterior migrated disc fragments.

INTRODUCTION

Migration of the sequestrated disc can be directed anteriorly, posteriorly, or laterally to the theca sac. The herniated disc fragments frequently migrate within the spinal canal usually in the rostral, caudal, and lateral directions2,12). The fragment migrating posteriorly through multiple natural barriers is rarely seen, and cauda equine syndrome (CES) caused by such migration is exceptionally rare2,9,10). All the reported cases of CES included previous worsening back pain or other neurologic signs before manifestation of overt paraplegia. However, the authors experienced a case of complete paraplegia after awakened without any previous neurological signs or symptoms.

CASE REPORT

A 74-year old man, who had no significant neurologic signs previously, visited our emergency center with paraplegia of both lower extremities that had occurred suddenly when awakened. On the initial neurologic examination, he was paraplegic, suffering from urinary retention and decreased anal tone. His sensory perception was declined below L1 dermatome. The knee reflex and the ankle reflex were lost. He had no prior trauma injury experiences before the admission without history of any other systemic symptoms like fever or weight loss.

The clinical findings suggested that CES might occur due to acute lumbar disc herniation, tumor, or epidural abscess. A foley catheter was anchored to preserve residual bladder function, and high-dose methylprednisolone therapy was carried out as initial management.

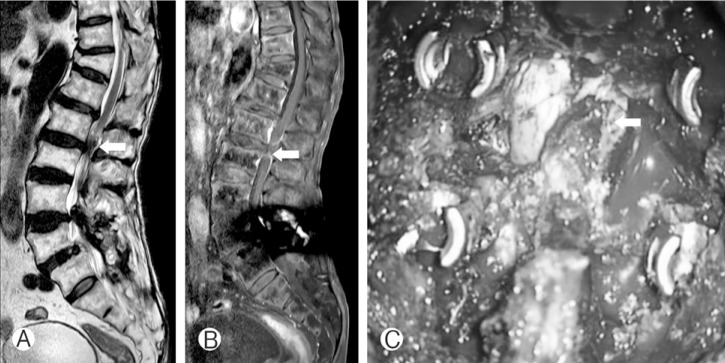

Plain radiographs of the lumbar spine showed L5-S1 posterior lumbar fusion after a traffic accident in 2004. On MRIs showing the posterior epidural space as a large low-intensity lesion on T2-weighted axial images and peripheral rim enhancement on Gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted MRI at L2-3 level, the theca sac and the conus medullaris seemed to be posteriolaterally displaced. We initially regarded this lesion as epidural abscess, epidural hematoma, tumor, or acute lumbar disc herniation. Epidural abscess and tumor were excluded because the patient's inflammatory markers were within normal range and no prior tumor had been diagnosed in other organs. Regardless of its origin, urgent operation was indispensable in order to alleviate neurological symptoms and we planned intra-operative biopsy to identify the lesion.

We performed emergent decompression and posterior lumbar interbody fusion. The decompression was conducted with bilateral complete laminectomies and facectectomies. After removal of the ligamentum flavum, right posterior migration of the lumbar intervertebral disc at L2-3 was observed, a migration that clearly compressed the right L3 nerve root. The removed fragment was originated with the intervertebral disc, confirmed by postoperative histopathology. The patient completely recovered from the previous neurological symptoms on 3 months' follow-up after the operation (Fig. 1).

DISCUSSION

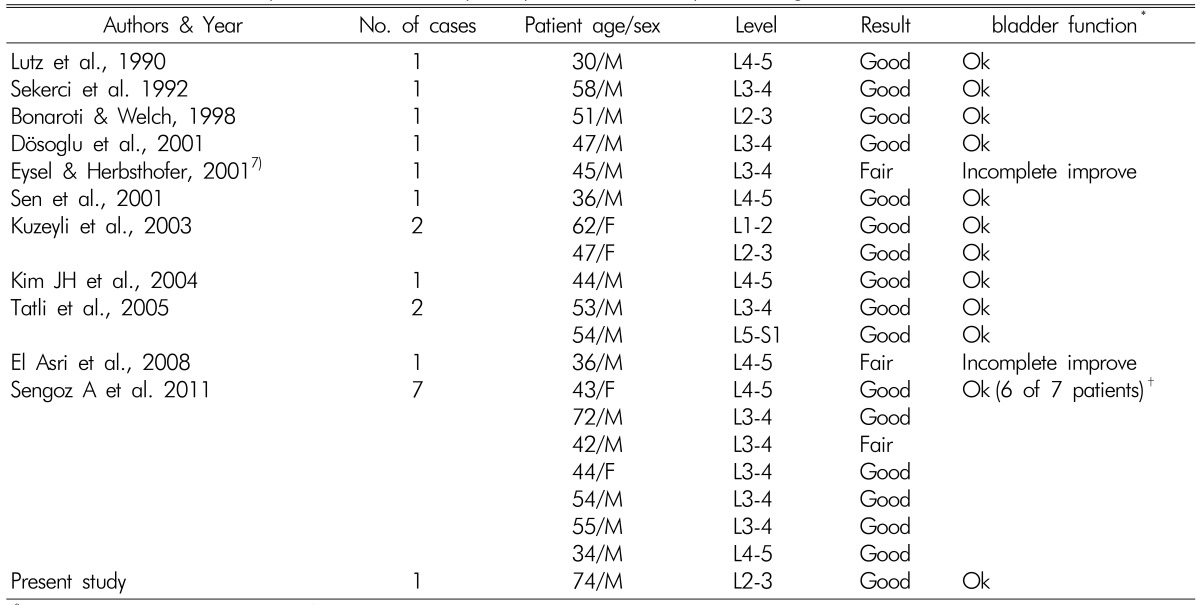

Posterior epidural disc fragment migration has been reported only rarely, and posterior migration causing CES is exceptionally rare2,9,10). Based on the literature review to date, a total 20 patients have been reported for CES by the posterior epidural migrated disc fragments (Table 1)

Literature review of patients with cauda equina syndromes caused by dorsal migration of lumbar intervertebral disc

The rare occurrence of this condition may be explained by the structural characteristics of this region. There are anatomical barriers to posterior migration of the sequestrated disc fragment. Schellinger et al.12) described the sagittal midline septum that spans between the vertebral body and the posterior longitudinal ligament, a septum that limits side-to-side migration of the disc8). Once a fragment transgresses the delicate connective tissue membrane, the peridural membrane or the lateral membrane, the epidural fat, the epidural venous plexus, and the nerve root itself presumably act as impediments to further posterior migration2).

Kuzeyli et al.7) reported that a 62-year-old woman developed acute lumbago and weakness after lifting a heavy load. In the course of 25 days, her low back pain and weakness increased. El Asri et al.5) reported that a 42-year-old man presented with three-year history of intermittent lumbago. He had experienced a progressive left-sided radiculopathy for one month. As seen in the reported cases, posterior migration of the sequestrated disc fragments frequently causes neurologic deficit, heralded by progressive neurological signs. But the authors experienced a case of complete paraplegia after awakened without any previous neurological signs or symptoms. The possibility of the disc rupture should be considered when patients complain symptoms seen above in emergency center. To our knowledge, this case is the only case reporting advanced neurological symptom without any previous manifestations.

Definite diagnosis of the posteriorly located disc fragments is difficult because the radiologic images of the disc fragments may mimic those of other more common posterior epidural lesions4,5,10). Thus, infections, tumors, degenerative diseases, traumas, and iatrogenic pathologies at the same anatomical location should also be considered12).

The first choice of imaging to evaluate cauda equina compression is MRI3,7,8). The disc fragment is generally hypointense on T1-weighted scans and hyperintense in 80% of cases on T2-weighted scans when compared to degenerated disc of origin12). The remaining 20% has isointense signal intensity related to the degenerated disc on T2-weighted images, as seen in our case3). Gadolinium-enhanced MRI should be performed if possible, as most of the migrate disc fragments show peripheral rim enhancement. An enhancement is caused by an inflammatory response with granulation tissue and newly formed vessels around the sequestrated tissue that lead to hyper-hydration of the disc fragment2,6). Typically, the center of the disc herniation dose not become enhanced11).

According to the literature review, the surgical outcomes of CES caused by dorsal migration of the sequestrated disc fragment are better than those of CES caused by conventional disc protrusion. CES is considered an absolute indication for acute surgical treatment of lumbar disc herniation. Timing of surgical decompression is controversial, with results in certain studies showing that delayed surgery may provide a satisfactory outcome, and recovery of function may not be related to the time to surgical intervention1). However, most reports suggest that early surgery should be the first choice to prevent severe neurologic deficits and to improve clinical outcome in paraplegia caused by posterior epidural migration6,7). Deciding to conduct unilateral hemilaminectomy, total laminectomy, or fusion should be based on the size of the lesion7). In our case, L2 total laminectomy and posterior lumbar interbody fusion was performed in order to avoid nerve root injury and L2-3 instability.

Data show that posterior epidural migration mostly occurs in the upper and middle lumbar regions, a situation that may be explained by insufficiency of the ligaments and other structures can facilitate dorsal migration of the disc fragment at the upper and middle lumbar levels13). According to Sengoz et al.13), more frequent occurrence of posterior migration at L3-4 may be due to the difference from other levels in the anatomical association between the disc space and the nerve root. The L3-4 level is the only one at which the disc space is actually in the horizontal plane, and anatomical association between the nerve root and the disc space may result in a decrease in the barrier role of the nerve root at this level12).

CONCLUSION

All the reported cases of CES showed that the patients had previous neurologic signs or symptoms before overt paraplegia. As of present, this case is the only one reporting complete paraplegia after awakened without any previous neurological signs or symptoms. Because posterior epidural disc fragment migration is difficult to be definitely diagnosed, early surgery can be the first choice to prevent severe neurologic deficits if posterior migrated disc is suspected.