Proximal Junctional Failure in Adult Spinal Deformity Surgery: An In-depth Review

Article information

Abstract

Adult spinal deformity (ASD) surgery aims to correct abnormal spinal curvature in adults, leading to improved functionality and reduced pain. However, this surgery is associated with various complications, one of which is proximal junctional failure (PJF). PJF can have a significant impact on a patient’s quality of life, necessitating a comprehensive understanding of its causes and the development of effective management strategies. This review aims to provide an in-depth understanding of PJF in ASD surgery. PJF is a complex complication resulting from a multitude of factors including patient characteristics, surgical techniques, and postoperative management. Age, osteoporosis, overcorrection of sagittal alignment, and poor bone quality are identified as significant risk factors. The clinical implications of PJF are substantial, often requiring revision surgery and causing a considerable decrease in patients’ quality of life. Prevention strategies include careful preoperative planning, appropriate patient selection, and optimization of surgical techniques. Treatment often necessitates a multifaceted approach, including surgical intervention and the management of underlying risk factors. Predictive modeling is an emerging field that may offer a promising avenue for the risk stratification of patients and individualized preventive strategies. A thorough understanding of PJF’s pathogenesis, risk factors, and clinical implications is essential for surgeons involved in ASD surgery. Current preventive measures and treatment strategies aim to mitigate the risk and manage the complications of PJF, but the complication cannot be entirely prevented. Future research should focus on the development of more effective preventive and treatment strategies, and predictive models could be valuable in this pursuit.

INTRODUCTION

Adult spinal deformity (ASD) encompasses a wide spectrum of conditions characterized by abnormal alignment and curvature of the spine in the sagittal or coronal planes [1-3]. These deformities can be the result of a variety of underlying conditions, such as scoliosis, kyphosis, spondylolisthesis, and degenerative changes related to aging [1-3]. ASD can lead to significant disability, reducing quality of life due to pain, reduced mobility, and decreased ability to carry out activities of daily living [1-3].

Given the aging global population, the prevalence of ASD is increasing, leading to a greater number of surgeries performed to correct these deformities and restore spinal alignment [1-3]. However, these procedures are complex and carry a significant risk of complications. Among these, proximal junctional failure (PJF) is one of the most severe, often requiring additional surgeries and significantly affecting the patients’ postoperative course and quality of life [4-12].

This review aims to elucidate the complexities of PJF, including its definition, pathogenesis, incidence, risk factors, clinical implications, preventive strategies, and treatment methods while exploring the future directions of research in this field.

DEFINITION AND CLASSIFICATION OF PJK/PJF

PJF represents a severe form of proximal junctional kyphosis (PJK), a postoperative complication characterized by an increase in the kyphotic angle at the junction between the fused and the adjacent unfused vertebrae. However, while PJK refers to this radiographic change, PJF involves additional serious complications. The main difference between PJK and PJF lies in the extent of the problem and its clinical impact. While PJK primarily involves radiographic changes (increased kyphotic angle at the junctional level), PJF represents a mechanical failure at the junction. This failure could involve fractures, listhesis, hardware failure, and is typically associated with significant clinical symptoms and often necessitates surgical revision. While PJK and PJF are related entities and part of a continuum, PJF represents a more severe and clinically impactful condition that often necessitates more aggressive interventions. These definitions are crucial in guiding therapeutic strategies and assessing outcomes in ASD surgery.

1. Proximal Junctional Kyphosis

PJK is essentially a radiographic diagnosis, characterized by an increase in the kyphotic angle between the lower endplate of the upper instrumented vertebra (UIV) and the upper endplate of the vertebra 2 levels above the UIV. A kyphotic angle increase of more than 10° to 20°, depending on the definition used, is typically considered indicative of PJK [13-16]. This change may or may not be accompanied by clinical symptoms.

2. Proximal Junctional Failure

PJF is considered a severe form of PJK that is associated with mechanical failure at the proximal junction of a spinal instrumentation. It is defined by the presence of one or more of the following [4,8,17-21]:

(1) Fracture of the UIV or the vertebra 1 level above (UIV+1)

(2) Failure of the posterior elements of UIV or UIV+1 leading to listhesis

(3) Neurological deficit

(4) The need for revision surgery due to clinical deterioration While there’s no universal classification, PJF might be categorized based on the type and severity of the mechanical failure and clinical symptoms. Recently, PJF is widely recognized as the any form of PJK requiring revision surgery [4,8,17-21].

Several classification systems have been described. Among them, the Yagi-Boachie PJK/PJF classification is a widely recognized system for categorizing PJK/PJF based on the pathogenesis [6-8]. The classification is as follows (Fig. 1).

Representative radiographs illustrating the types of PJK according to the Yagi-Boachie PJK/PJF Classification System. (A) Representative radiograph of Yagi-Boachie type 1 PJK: ligamentous failure. (B) Representative radiograph of Yagi-Boachie type 2 PJK: bone failure. (C) Representative radiograph of Yagi-Boachie type 1 PJK: implant and bone interface failure. PJK, Proximal Junctional Kyphosis; PJF, proximal junctional failure.

1) Type 1: disc and ligamentous failure

This type is characterized by a kyphotic deformity that occurs at the junctional level but without any signs of instrumentation failure, screw pullout or junctional listhesis (displacement between UIV and UIV+1). This type is typically managed conservatively with observation, pain management, and physical therapy.

2) Type 2: bone failure

This type involves a kyphotic deformity with fracture of either UIV or UIV+1 vertebra and can cause junctional listhesis. Patients with type 2 PJK often require revision surgery to extend the fusion and restore spinal alignment.

3) Type 3: implant/bone interface failure

This type is characterized by a kyphotic deformity that occurs at the junctional level due to bone/implant interface failure, such as pedicle screw loosening. Type 3 PJK typically asymptomatic and does not necessitate revision surgery.

By using this classification, clinicians can accurately describe the severity of PJK, predict potential complications, and determine the most appropriate treatment.

INCIDENCE OF PJF

Although the incidence of PJK is relatively well-documented, the incidence of PJF is less so due to its definition variability and the need for revision surgery to confirm the diagnosis. The reported incidence rates range between 2% and 18% following ASD surgery [8,12,17,22]. A multicenter study by Crawford et al. [22] showed an incidence rate of PJF of approximately 7% at 2 years. Another study by Yagi et al. [8] suggested a slightly higher incidence, reporting a rate of 8.8%. However, Maruo et al. [12] found an incidence rate of 2.4% after 2 years. The variability in incidence rates can be attributed to the differences in the patient population, surgical techniques, and the specific definitions used for PJF.

PATHOGENESIS AND RISK FACTORS OF PJF

The exact pathogenesis of PJF remains unclear, yet it is a multifactorial complication related to an intricate interplay of biomechanical, surgical, patient-related, and radiographic factors:

1. Biomechanical Factors

A notable transition from a rigid, instrumented spine to a more flexible, noninstrumented area produces a “stress-riser” at the junction. The subsequent change in rigidity, coupled with increased mechanical stress and movement, can lead to junctional region failure [23-25].

2. Surgical Factors

Surgical factors such as overcorrection of the spinal deformity, aggressive facetectomy at the UIV, or the selection of an unsuitable UIV (e.g., in a region with preexisting degenerative changes or deformity) can heighten PJF risk.26-29

3. Patient-Related Factors

Certain patient characteristics, such as advanced age, osteoporosis, and high body mass index (BMI), are linked to a heightened risk of PJF. These factors are likely attributed to the diminished bone quality and increased mechanical stress they induce [20,26-28,30].

Recognizing these risk factors is vital for effective preoperative planning, patient counseling, and the development of strategies to potentially mitigate the risk of PJF. The interplay of these factors can often be complex, which necessitates a comprehensive, holistic approach when considering these risks. However, the development of PJF is a significant complication following ASD surgery, making it crucial to understand its definition, pathogenesis, and risk factors for effective prevention and management strategies.

ROLE OF RADIOLOGICAL PARAMETERS AND PREDICTIVE MODELS IN PJF

Implementing various predictive models and radiological parameters can provide critical insights into the management and prevention of PJK and PJF. These parameters serve as important guidelines for optimal correction in ASD surgery. Here, we elaborate on the Scoliosis Research Society (SRS)-Schwab classification, age-adjusted sagittal alignment goals, the global alignment and proportion (GAP) score, and the Roussouly algorithm. [2, 6, 7, 9, 31-40]

1. SRS-Schwab Classification

The SRS-Schwab classification system is a widely recognized tool for quantifying the severity of ASD [34]. It considers 3 sagittal plane modifiers (sagittal vertical axis, pelvic tilt, and pelvic incidence minus lumbar lordosis) and quantifies deformity based on these modifiers. The strength of this system lies in its incorporation of global parameters, enabling comprehensive evaluation of spinal alignment. However, it does not provide explicit guidance on age-adjusted alignment goals or predict the risk of complications such as PJF.

2. Age-Adjusted Sagittal Alignment Goals

Age-adjusted sagittal alignment aims to guide spinal correction surgery by accounting for natural changes in spinal alignment with aging. According to a study by Lafage et al. [35], this age-adjusted model was validated in terms of PJF and clinical outcomes in ASD. However, it has limitations and may not be universally applicable to all patients. They found a higher incidence of PJK in older age groups and suggested the incorporation of age-specific alignment targets into preoperative planning to optimize surgical outcomes and prevent PJK.

3. GAP Score

The GAP score is another important tool that provides guidelines for individualized patient alignment to achieve balanced sagittal alignment and minimize complications. Yilgor et al. [36] developed and validated the GAP score, demonstrating high predictive accuracy for mechanical complications. Patients with proportioned spinopelvic alignment according to the GAP score had a significantly lower rate of mechanical complications compared to those with disproportioned alignment. Conversely, a study by Yagi et al. [37] found that the GAP score was not predictive of mechanical failure or revision surgery in an Asian cohort of patients with ASD, suggesting the need for further research to assess its predictive ability in different patient populations.

4. Roussouly Classification

The Roussouly classification is a 4-type classification based on the shape and alignment of the sagittal spinal profile [39]. It can assist surgeons in understanding the patient’s natural alignment and planning surgery accordingly. Although useful for assessing preoperative alignment, it does not inherently include any predictive elements for postoperative complications like PJF [40].

Each of these systems provides valuable insights into optimal correction goals and patient stratification in ASD surgery. However, none can singularly predict the occurrence of complications such as PJF. Therefore, a multifactorial approach, incorporating patient-specific characteristics, clinical variables, radiological parameters, and predictive models, is essential to provide the best surgical outcomes.

Each of these systems provides valuable insights into optimal correction goals and patient stratification in ASD surgery. However, none can singularly predict the occurrence of complications such as PJF. Therefore, a multifactorial approach, incorporating patient-specific characteristics, clinical variables, radiological parameters, and predictive models, is essential to provide the best surgical outcomes.

BONE QUALITY AND SARCOPENIA: THEIR ROLE IN PJK/PJF AFTER ASD SURGERY

Emerging evidence indicates that poor bone quality and muscle mass (sarcopenia) are significant risk factors for the development of PJF after ASD surgery, especially in the Asian population.

1. Bone Quality

Bone quality, often compromised in patients with low bone mineral density (BMD) or osteoporosis, has been identified as a crucial factor influencing the risk of PJF in recent studies.

Yagi et al. [41] conducted a propensity-matched analysis to investigate BMD as a risk factor for PJF in patients who underwent corrective surgery for ASD. They categorized the 113 ASD patients based on T scores into 2 groups: mildly low to normal BMD (M group) or significantly low BMD (S group). They found that PJF occurred in 19% of patients, but significantly more frequently in the S group compared to the M group (33% vs. 8%, respectively). The odds ratio of 6.4 indicated a notable risk for PJF in the group with lower BMD, highlighting the necessity of considering prophylactic treatments for patients with low BMD during ASD correction.

Building on this, Kuo et al. [42] conducted a retrospective chart review to assess the predictive power of the MRI-based vertebral bone quality score (VBQ) for PJF after corrective surgery for ASD. In a sample of 116 patients who underwent surgery involving 5 or more thoracolumbar levels, they found that patients with higher VBQ scores were significantly more likely to develop PJF. Their multivariate analysis found that the VBQ score was the only significant predictor of PJF, with an increased odds ratio of 1.745 associated with higher VBQ scores, demonstrating a predictive accuracy of 94.3%.

Lastly, Mikula et al. [43] explored the relationship between BMD, as estimated by Hounsfield units (HU), and PJF in the upper thoracic spine. The study found that among a total of 81 patients who underwent instrumented fusion, 33% developed PJF. On multivariable analysis, they discovered that a lower HU at the UIV/UIV+1 was the only independent predictor of PJF, with a lower HU indicating an increased risk. Patients with HU < 147 at the UIV/UIV+1 had a 59% rate of PJF, emphasizing the need to assess BMD using HU measurements to identify high-risk patients and implement preventive measures.

These studies underscore the critical role of bone quality in the onset of PJF, urging increased focus on bone health in the management and surgical intervention strategies for patients with ASD.

2. Sarcopenia

Recent research suggests a significant link between sarcopenia, a condition characterized by the loss of skeletal muscle mass and function, and various spinal disorders. A study conducted by Yagi et al. [6], aimed to explore the role of the multifidus (MF) and psoas (PS) muscles in the maintenance of global spinal alignment in patients with degenerative lumbar scoliosis (DLS). In a cohort of 120 female patients, the cross-sectional areas (CSAs) of the MF and PS muscles were significantly smaller in the DLS group compared to the lumbar spinal stenosis group. The DLS group also exhibited a larger percentage difference in CSA between the right and left sides. Importantly, the average CSA of the MF showed moderate correlations with global spinal alignment and spinopelvic alignment in the DLS group. The MF CSA was also found to be correlated with postoperative kyphosis progression at the unfused thoracic vertebrae in the DLS group.

In a different study by Guo et al. [44], the characteristics of paravertebral muscles (PVMs) in ASD patients were studied with regard to pelvic incidence minus lumbar lordosis (PI–LL) match or mismatch. Out of 67 ASD patients, the PVM on the concave side was found to be larger than on the convex side in both PI–LL match and mismatch groups. The mismatch, however, exacerbated this asymmetry. More concerning was that the average degeneration degree of the MF, visual analogue scale scores for pain, symptom duration, and Oswestry Disability Index for disability were significantly higher in the PI–LL mismatch group. Babu et al. [45] conducted a retrospective study to determine if sarcopenia is an independent risk factor for complications in ASD patients undergoing pedicle subtraction osteotomy (PSO). In a cohort of 73 ASD patients, it was found that patients with complications had a lower psoas-lumbar vertebral index (PLVI) on average compared to those without complications. Patients with lower PLVI values had significantly greater odds of developing complications such as proximal junctional kyphosis, wound infection, and dural tear. Krenzlin et al. [46] conducted a study to examine the impacts of sarcopenia and bone density on implant failures (IFs) and complications in patients with spondylodesis due to osteoporotic vertebral fractures (OVFs). Out of 68 patients with OVFs, sarcopenia was detected in 47.1%, myosteatosis in 66.2%, and osteoporosis in 72%. Lower skeletal muscle area (SMA) z-scores adjusted for height and BMI (zSMAHT) were significantly associated with IFs, suggesting that the presence of sarcopenia and osteoporosis increased the likelihood of an IF. The study also established sarcopenic obesity as the main determinant for IF occurrence.

Recognizing and addressing these risk factors is crucial. Improving bone quality and treating sarcopenia could potentially reduce the risk of PJF. This could involve comprehensive management including nutritional supplementation, pharmacotherapy for osteoporosis, and physical rehabilitation to improve muscle mass and strength. Further research is necessary to determine the best strategies to manage these risks.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS OF PJF

PJF can significantly impact patients’ quality of life due to associated pain, functional impairment, and the potential requirement for revision surgery. Studies have shown that patients with PJF report lower scores on health-related quality of life measures compared to those without PJF. In severe cases, PJF can lead to neurological deficits, which can have debilitating outcomes [5-8,10,11,47].

1. Pain and Physical Discomfort

One of the most immediate implications of PJF is the significant pain and discomfort it can cause. This can severely restrict a patient’s mobility and physical capabilities. Often, the pain is localized at the upper part of the instrumentation and can be exacerbated by movement. While the exact incidence is challenging to quantify due to variations in individual pain thresholds and reporting, most patients with PJF experience significant pain and discomfort [5-8,10,11].

2. Neurological Complications

The reported incidence of neurological complications related to PJF varies widely, with some studies suggesting an incidence of around 10%–15%. For example, if the failure involves a fracture of the UIV or the UIV+1 and there is posterior displacement, the spinal cord or nerve roots could be compressed, leading to symptoms such as numbness, weakness, or even paralysis [5-8,10,11].

3. Revision Surgery

PJF often necessitates revision surgery, which can carry its own set of risks and complications. The reported rate of revision surgery due to PJF is around 10%–20% [8,17,29]. This includes a higher risk of infection, blood loss, and perioperative complications. The additional surgery can also lead to prolonged hospital stays and increased healthcare costs. The need for revision surgery is a significant clinical implication of PJF [5-8,10,11].

4. Impaired Quality of Life

The combination of pain, reduced mobility, neurological symptoms, and the psychological stress of facing additional surgeries can significantly impair a patient’s quality of life [5-8,10,11]. This can affect various aspects of life, including mental health, social relationships, and the ability to work or perform daily activities. The incidence of impaired quality of life is difficult to quantify as it involves subjective and varied measures. However, most patients with PJF are likely to experience some decrease in quality of life due to pain, disability, and the need for further surgery.

5. Impaired Spinal Alignment

PJF can lead to a loss of the corrective alignment achieved during the initial surgery, leading to a recurrence of the original deformity symptoms. This can further exacerbate pain and disability [6,7].

6. Psychological Impact

The diagnosis of PJF, coupled with the potential requirement for additional surgery and the associated complications, can have a significant psychological impact on patients, leading to stress, anxiety, and potentially depression [5-8,10,11].

Overall, PJF can have profound clinical implications affecting various aspects of a patient’s life, highlighting the importance of appropriate preventive and treatment strategies.

PREVENTION STRATEGIES FOR PJK/PJF

Prevention strategies are primarily directed towards risk modification. While PJF cannot be entirely prevented, several strategies may help to reduce its risk. This includes optimization of bone health, careful patient selection, appropriate surgical technique, and maintaining a balanced spinal alignment. The role of prophylactic vertebroplasty, cement augmentation of the UIV, and the use of hook or transitional rods are currently being investigated [9].

1. Preoperative Planning and Patient Selection

Careful patient selection and preoperative planning are crucial. This includes optimizing the patient’s health before surgery, managing comorbidities such as osteoporosis using teriparatide, and carefully assessing the patient’s spinal alignment [6-8,48,49]. Correct selection of the level of the UIV based on individual patient anatomy and alignment can also reduce the risk of PJF [50].

2. Management Strategies for Improving Bone Quality in ASD Surgery

Management strategies for improving bone quality, especially in the context of ASD surgery, are essential to prevent instrumentation-related complications. Both in preoperative and postoperative phases, several pharmacological therapies have shown promise. These therapies primarily aim to either increase bone formation or decrease bone resorption, thereby enhancing overall bone density and quality. Recently, several therapeutic agents such as teriparatide, romosozumab, abaloparatide, and denosumab have shown promise in enhancing bone quality and preventing complications [51-57].

Teriparatide, a recombinant form of parathyroid hormone, is known to enhance bone formation. A study by Yagi et al. [51] revealed that teriparatide therapy initiated immediately after surgery improved the volumetric BMD (vBMD) and fine bone structure at the vertebra above the UIV+1. After 6 months of treatment, the teriparatide group showed a significant increase in hip-BMD and vBMD at UIV+1 compared to the control group. Moreover, a lower incidence of vertebral-failure-type proximal junctional kyphosis (PJK type 2) was reported in the teriparatide group at the 2-year follow-up, suggesting its potential in preventing PJK.

Abaloparatide, similar to teriparatide, abaloparatide is an anabolic agent that promotes bone formation. Clinical trials have shown its efficacy in reducing the risk of fractures and improving BMD in patients with osteoporosis [47]. Further studies are warranted to validate its utility in the preoperative setting of ASD surgery.

Romosozumab, a monoclonal antibody, functions by increasing bone formation and decreasing bone resorption. It has shown beneficial effects in increasing BMD and reducing fracture risk. This could potentially translate to a reduced risk of instrumentation failure in ASD surgery.

Denosumab, another monoclonal antibody, inhibits bone resorption by binding to RANKL (receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-β ligand). Studies have shown it increases BMD and decreases vertebral and nonvertebral fractures in postmenopausal women. It could provide similar benefits in the context of ASD surgery.

Bisphosphonates, an antiresorptive agents inhibit osteoclast-mediated bone resorption, thus improving bone quality. Several studies have demonstrated that bisphosphonates can reduce the risk of postoperative vertebral fractures and enhance fusion rates, while the effect is limited.

Further, combining therapies could offer superior outcomes. For instance, combining teriparatide and denosumab has been shown to produce a more significant increase in BMD than either agent alone.

In conclusion, employing these therapies in both the preoperative and postoperative phases could contribute to enhanced bone quality and lower the risk of postoperative complications in ASD surgery. However, the application of these therapies should be individualized and based on thorough patient evaluation.

3. Surgical Technique

1) Mitigating overcorrection and limiting fusion length

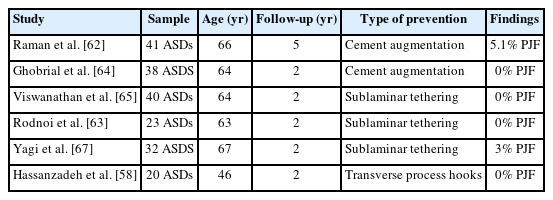

Surgical techniques can be fine-tuned to help prevent PJF. These adjustments could involve mitigating the overcorrection of sagittal alignment, favoring a gradual correction of deformities over an abrupt change, and aiming to limit the length of fusion where viable. Attention is increasingly being drawn to prophylactic measures, such as vertebroplasty, cement augmentation, and the implementation of hooks, transitional rods, or sublaminar tethering (Table 1) [19,23,50,58-67].

2) Cement-augmented pedicle screws at the UIV and UIV+1

The application of cement-augmented pedicle screws at the UIV and UIV+1 is a strategic approach aimed at reinforcing the stability of fixation, especially beneficial for patients with diminished bone quality [19,61,62]. Cement augmentation notably enhances the pullout strength of pedicle screws, which is advantageous for patients with low BMD or osteoporosis. Numerous studies have suggested that by fortifying the fixation at the UIV and UIV+1, cement augmentation might help mitigate mechanical stress at these junctional levels, potentially lowering the risk of PJF. While the initial cost of cement-augmented pedicle screws may be higher than traditional pedicle screws, the potential decrease in revision surgeries due to PJF could render this approach cost-effective in the long run. However, it’s important to acknowledge potential drawbacks associated with this method. A risk exists for cement leakage into the spinal canal or vascular system, which can lead to serious complications, including neurological deficits or pulmonary embolism. Additionally, it is theorized that cement augmentation increases the construct’s stiffness, which might redistribute increased stress to the adjacent levels and potentially result in adjacent segment disease. Furthermore, in situations where revision surgery becomes necessary, the extraction of cement-augmented pedicle screws could prove challenging and may possibly lead to supplementary complications.

3) Ligament augmentation using polyethylene tape at the upper instrumented levels

A newly described procedure to constrain excessive movement and reduce the likelihood of PJF is ligament augmentation at the upper instrumented levels using polyethylene tape [66-68]. In this technique, a polyethylene tape with high tensile strength and durability is looped around the spinous processes or lamina at the UIV and the adjacent level (UIV and UIV+1 or UIV+2). The tape is tensioned to a certain degree and secured, creating a posterior tension band effect (Fig. 2). This technique aims to provide additional support and stability to the junctional region, thereby reducing abnormal motion and stresses that could lead to PJF. The rationale behind this method is that it attempts to mimic and augment the function of the posterior tension band—the supraspinous and interspinous ligaments—which are often disrupted during surgery. However, while initial studies show promising results, long-term data and larger studies are needed to validate the safety and efficacy of this technique. Furthermore, technical considerations such as the optimal tension on the tape and the ideal anchoring points for maximum effect are yet to be established.

4) Contouring of the terminal rod and fusion length considerations

The contouring of the terminal rod represents another intraoperative technique designed to circumvent the occurrence of acute junctional kyphosis between the UIV and UIV+1, offering a potential advantage over the use of a flat terminal rod (Fig. 3). Moreover, the surgeon’s decision to terminate the construct at a specific level should be carefully considered, given that extended fusions are known risk factors for PJF.

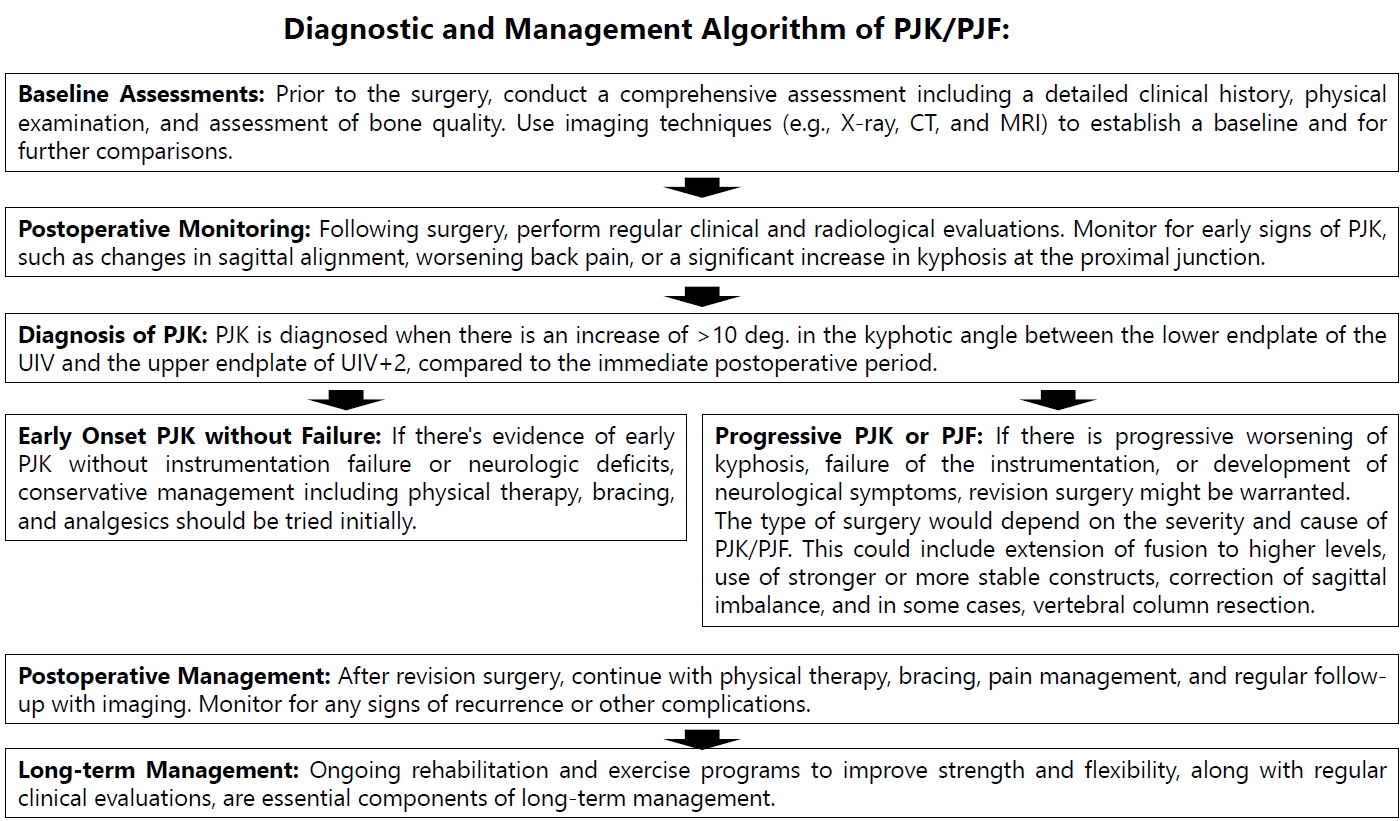

TREATMENT OF PJF

Treatment of PJK often necessitates a multidisciplinary approach (Fig. 4). The initial step often involves conservative measures, including pain management, bracing, and physiotherapy [6-8]. However, these measures may be insufficient in PJF cases. Surgical intervention is considered in patients with progressive neurological deficits, persistent pain, or those who experience significant deterioration in their quality of life [6-8]. Additionally, further PJF commonly developed after revision surgery for PJF [8,69-71]. Surgery typically involves extension of the fusion to more proximal levels, revision of the instrumentation, or even vertebral column resection (VCR) in severe cases. Revision surgery for PJF after ASD surgery is a complex procedure and should be tailored to the individual patient’s anatomy, symptoms, and overall health status. Various strategies can be utilized depending on the specifics of the PJF presentation.

Diagnostic and management algorithm of PJK/PJF. PJK, Proximal Junctional Kyphosis; PJF, proximal junctional failure; CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; UIV, upper instrumented vertebra.

1. Surgical Approach

The surgical approach to PJF revision surgery can be posterior, anterior, or a combined approach. The decision depends on several factors, including the location and severity of the failure, the need for neural decompression, the patient’s overall health, and the surgeon’s expertise [32,70,71].

2. Extension of Fusion

One common strategy in PJF revision surgery is extending the fusion to more proximal levels. However, it’s important to be mindful of the potential for creating additional stress at the new junctional level [33,69].

3. Osteotomies

In cases where PJF has resulted in significant kyphosis at the junctional level, an osteotomy may be necessary to correct the alignment. This could involve a PSO or a VCR, depending on the severity of the deformity [32,71].

4. Reinforcement of UIV and UIV+1

Reinforcing the fixation can also be beneficial in PJF revision surgery to avoid further PJF. This could involve using larger or longer pedicle screws, adding additional screws or hooks, posterior laminar tethering, or using cement augmentation to decrease the integrity of the posterior ligamentum complex [19,23,50,58-63].

5. Anterior Column Support

In some cases, particularly where there has been substantial vertebral body collapse or fracture, adding anterior column support can be beneficial. This could involve an anterior or lateral lumbar interbody fusion or the placement of a cage [32,72,73].

6. Addressing Bone Health

In patients with osteoporosis or other conditions affecting bone health, it’s crucial to address this as part of the revision strategy. This could involve medical management such as teriparatide and bisphosphonate to improve bone density or the use of bone grafts or bone morphogenetic proteins to enhance fusion [27,44,63].

It’s important to note that revision surgery for PJF carries significant risks, and the decision to proceed should be made after careful consideration of the potential benefits and risks. Furthermore, the best strategy will depend on the individual patient’s situation and the surgeon’s judgement and expertise.

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE IN PREDICTING AND PREVENTING PJK/PJF: INSIGHTS FROM RECENT STUDIES

Artificial intelligence (AI) holds great promise in the management of spinal conditions such as PJK and PJF. Recent research has been focused on leveraging AI for predictive analysis, imaging assessment, and personalized treatment planning [74-79].

1. Predictive Analysis

In a multicenter study, Scheer et al. [75] developed a predictive model for PJK and PJF in ASD surgery, achieving an accuracy of 86.3%. They identified several factors, including age, lowest instrumented vertebra (LIV), preoperative sagittal vertical axis, UIV implant type, preoperative pelvic tilt, and preoperative PI–LL, as strong predictors. This model can aid in preoperative decision-making and risk stratification in ASD surgery. Yagi et al. [76] further validated and refined this predictive model by including BMD as an additional variable. Their model achieved 100% accuracy in the testing sample. Key predictors identified were pelvic tilt, BMD, LIV level, UIV level, PSO, global alignment, BMI, PI–LL, and age. This updated model offers a more comprehensive risk profile for PJF in the perioperative period. Another study by Noh et al. [77] developed a machine learning model based on GAPB (GAP scoring with BMI and BMD) factors for predicting mechanical complications in ASD surgery. The random forest algorithm employed in this study displayed the highest performance, suggesting its utility in surgical risk prediction.

2. Imaging Analysis

AI has also shown potential in imaging analysis. Grover et al. [78] evaluated an AI-based algorithm for determining sagittal balance parameters in patients with and without spinal instrumentation. The algorithm demonstrated excellent agreement with human raters, particularly on preoperative images, suggesting its efficiency for large-scale imaging analysis.

Similarly, Orosz et al. [79] introduced an AI algorithm that accurately measures spinopelvic parameters on lumbar radiographs. The AI measurements displayed excellent interrater reliability and provided precise measurements, proving it to be a valuable tool for clinical practice and research.

Taken together, these studies demonstrate the significant potential of AI in predicting PJK/PJF risk and guiding surgical decision-making. It offers the advantage of analyzing large datasets and imaging efficiently, accurately, and objectively. However, further research is needed to ensure the generalizability of these AI models across diverse patient populations and settings.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

While considerable progress has been made in understanding PJF, significant knowledge gaps still exist. Future research should focus on further elucidating the pathophysiology of this complex disorder. Additionally, it is crucial to establish a standard definition of PJF to facilitate consistent reporting and comparison across studies.

The development and validation of a risk prediction model could help identify patients at high risk for PJF preoperatively. This could guide surgical decision-making and patient counseling, and aid in the development of personalized prevention strategies. Moreover, investigating the role of novel biomarkers and advanced imaging techniques in predicting PJF warrants attention. In the therapeutic realm, efforts should be directed towards refining surgical techniques and the development of advanced spinal implants to prevent PJF. Additionally, assessing the efficacy of minimally invasive surgery (MIS) in preventing PJF could be promising, as MIS techniques are associated with less tissue damage and potentially fewer postoperative complications.

Finally, conducting long-term follow-up studies will help understand the natural history of PJF and the true impact of various prevention and treatment strategies on patient outcomes.

CONCLUSION

PJF is a multifaceted complication of ASD surgery with significant implications for patients’ quality of life. Our understanding of its pathogenesis is still evolving, but current efforts are directed towards developing effective prevention and treatment strategies. Future research is critical to filling the existing knowledge gaps and improving patient outcomes in ASD surgery.

Notes

Conflict of Interest

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding/Support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author Contribution

Project administration: MY; Writing - original draft: MY; Writing - review & editing: KY, NF, HF, SE.