Radiological and Clinical Outcomes of Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion in Older Patients: A Comparative Analysis of Young-Old Patients (Ages 65–74 Years) and Middle-Old Patients (Over 75 Years)

Article information

Abstract

Objective

Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) is the most commonly performed procedure for degenerative cervical spondylosis. Because of its relatively low invasiveness and surgical procedure, old age is not regarded as an exclusion criterion for ACDF. However, very few studies have been conducted on the radiological and clinical outcomes of ACDF in older patients. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the radiological and clinical outcomes of ACDF in older patients.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed 48 patients (> 65 years) who underwent ACDF from January 2011 to December 2015. We divided the patients into 2 groups: young-old age group (65–74 years) and middle-old age group (≥ 75 years). Cervical lateral radiographs taken in the neutral standing position were evaluated preoperatively (PRE), on postoperative day 7 (POST), and at the 1-year follow-up (F/U). The radiological parameters included cervical angle (CA: C2–7 Cobb angle), segmental angle, total intervertebral height, disc height, sagittal vertical axis (SVA), T1 slope (T1s), and range of cervical motion (extension CA minus flexion CA). Postoperative hospital days, comorbidities, complications, and clinical outcomes were also analyzed.

Results

We analyzed data from 48 patients (group A: n = 30 patients, 46 segments, mean age, 68.60 ± 3.36 years; group B: n = 18 patients, 23 segments, mean age, 79.22 ± 2.63 years). The surgical levels were as follows: C3/4, 4; C4/5, 7; C5/6, 10; C6/7, 29; and C7/ T1, 6 levels, and there were no significant between-group differences in the distribution. There were no significant between-group differences in the fusion and subsidence rates (fusion rate: group A, 76.2%; group B, 71.4%; p = 0.732; subsidence rate: group A, 34.8%; group B, 26.1%; p = 0.587). There was no longitudinal trend in the repeated-measurements analysis of variance test of the 2 groups of the PRE, POST, and F/U data for each radiological parameter. According to the paired t-test, T1 slope (T1s), SVA, and CA did not differ preoperatively and postoperatively. There was no statistically significant difference in visual analogue scale scores (axial, arm), the Neck Disability Index, or Odom’s criteria between the 2 groups (p = 0.448, p = 0.357, and p = 0.913).

Conclusion

There was no significant difference in radiological and clinical outcomes between young-old and middle-old patients. Middle-old age does not seem to be a limitation to ACDF, but larger-scale and longer-term studies are needed to confirm the findings of this study.

INTRODUCTION

Global populations have consistently increased over the past 50 years [1]. In the United States, the population of 62-years-olds and older grew by 21.2% between 2000 and 2010, this older age group was the subgroup with the fastest growth [2]. Additionally, the U.S. Census Bureau projected that the population of 65-yearolds will double between 2012 and 2050 [3]. Korea’s population aged 65 years and above has increased from 7% in 1999 to 11.8% in 2012 and is expected to increase to 14% in 2017 and 20.8% in 2026 [4]. Aging is associated with a rise in degenerative spinal disorders prevalence, thus, clinicians need to understand the pathophysiology of the spine in old age.

Degenerative cervical myelopathy (DCM) is a progressive disease caused by age-related degeneration of the facet joints, intervertebral disks, or vertebral bodies [5]. Because of the increased prevalence of DCM, cervical spine surgeries have been increasing for many years [6]. It is also reported that the risk of complication is higher for older patients or patients with more comorbidities [7]. However, these studies focused on posterior cervical spine surgery. There are no reports on the postoperative clinical and radiological outcomes of anterior cervical surgery in older patients.

In this study, we aimed to compare the postoperative clinical and radiological outcomes of anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) in young-old (65–74 years) and middle-old (≥ 75 years) patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Patient Population

Between January 2011 and December 2015, data from 190 patients who underwent ACDF for cervical spondylosis at a single institution were reviewed. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) patients with degenerative cervical spondylosis, who were not responding to medical treatment, (2) patients older than 65 years, and (3) patients who received a minimum follow-up (F/U) of more than 1 year. Patients with other disease entities such as trauma, tumor, infection, or patients with previous cervical operations were excluded. Patients were categorized into the young-old (65–74 years) and middle-old ( ≥ 75 years) groups and we evaluated them for fixed preoperative factors such as diabetes milieus, history of smoking, body mass index, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification.

2. Surgical Techniques

All the patients underwent surgery using the standard SmithRobinson anteromedial left-sided approach [8]. After the removal of the intervertebral disc with a careful endplate preparation, a high-speed electric drill and Kerrison punch were used to decompress the nerve roots by removing the osteophyte overgrowth on the uncovertebral joint and posterior lips of the vertebral body. We performed bilateral uncinated process resection, even in patients with unilateral symptoms, to eliminate the remnant osteophyte regrowth. After sufficient decompression, we applied a stand-alone polyetheretherketone cage (CORNERSTONE PSR, Medtronic Sofamor Danek, Memphis, TN, USA) filled with demineralized bone matrix or allograft bone graft (CORNERSTONE ASR) with anterior plating (ATLANTIS, Medtronic Sofamor Danek) under fluoroscopy. We attempted to position the cage on the anterior edge of the upper vertebra to prevent subsidence. After the release of the Caspar distractor, a manual pullout test confirmed the stability of the segments. After the surgery, all the patients were instructed to wear a soft collar for 2 months.

3. Radiological Evaluation

All radiological assessments were performed at 1-month intervals by an independent observer who was experienced in spinal diseases. Mean values were calculated and used in the statistical analyses. Lateral standing plain radiographs (neutral standing position facing forward) were performed at the following time points: preoperatively (PRE), immediately after surgery, postoperative day 7 (POST), every 3 months after surgery, and at the latest F/U examination. Lateral standing flexion/extension plain radiography was performed every 3 months starting at 6 months after surgery.

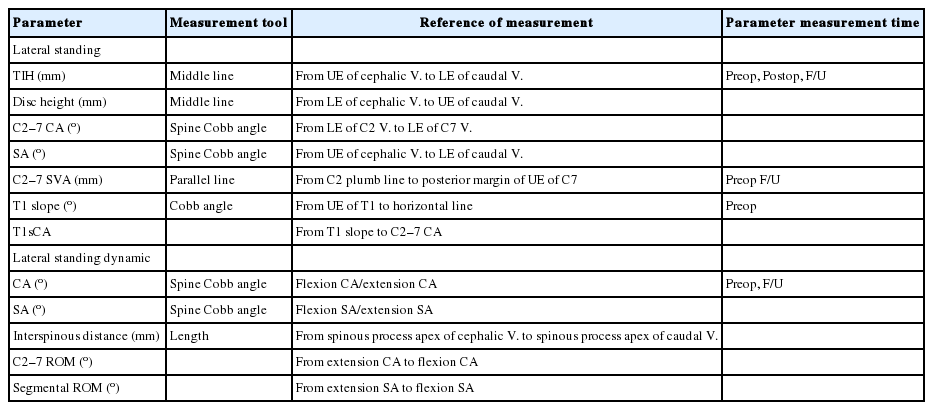

Parameters were measured using commercial software (Marosis 5.0, INFINITT Healthcare, Seoul, Korea) and are summarized in Table 1. The range of motion (ROM) was defined as the extension angle minus the flexion angle (Fig. 1). Alignment of cervical angle (CA: C2–7 Cobb angle) ≥ 0 was defined as lordosis. The difference between PRE and F/U values for each parameter was designated as the delta (Δ) value. For example, Δ CA was calculated as F/U CA minus PRE CA. Δ values were calculated for CA, segmental angle (SA), and SVA. We defined subsidence as Δ TIH (= POST TIH – F/U TIH) ≥ 3 mm (TIH, total intervertebral height). Pseudarthrosis was defined as segmental instability with a > 2 mm increase in the interspinous distance or a segmental ROM of > 2° on the flexion-extension lateral views at the most recent F/U [9]. Pseudarthrosis a complication that may occur after ACDF and is evaluated because neurological dysfunction and revision may be necessary [10].

Measurements of the radiological parameters. (A) Neutral lateral image. (B) Flexion lateral image. (C) Extension lateral image. SVA, sagittal vertical axis; TIH, total intervertebral height; SA, segmental angle; CA, C2–7 cervical angle; T1SCA, T1 slope minus CA; Flex, flexion; interspinous, interspinous distance.

4. Clinical Evaluation

Clinical evaluations included the Neck Disability Index (NDI), and visual analogue scales for the neck (VAS-neck) and arm pain (VAS-arm). The evaluations were performed pre- and postoperatively, and at F/U. At the last F/U, patients were evaluated according to Odom’s criteria, with ratings from excellent to poor [11]. Postoperative complications were also evaluated.

5. Statistical Analysis

The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to confirm the normal distribution (p> 0.05). Group differences (S vs. non-S; P vs. non-P) in radiological and clinical outcomes were evaluated using Student t-tests and Mann-Whitney U-tests for parametric and nonparametric continuous variables, respectively. Pearson correlation analyses were performed, even when only one parameter was normally distributed. Repeated-measure analyses of variances were performed to investigate longitudinal trends within T1s groups. A multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed using the backward likelihood ratio method. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 21.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA).

RESULTS

1. Patient Characteristics

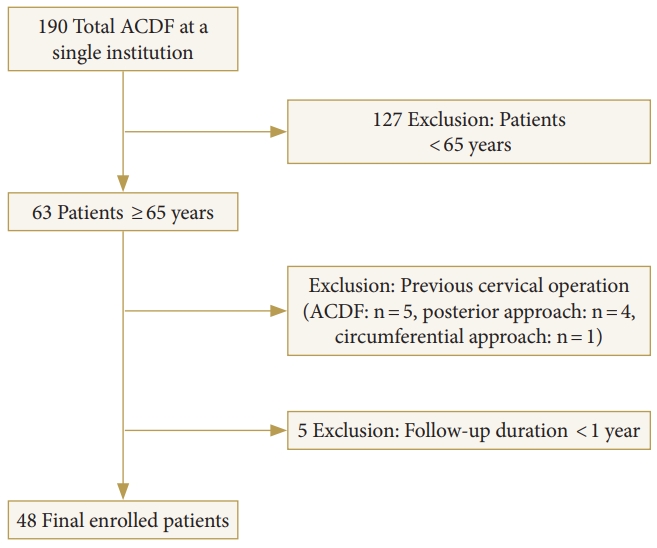

Forty-eight patients (36 men) met the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Fig. 2). Mean age at surgery was 72.6± 6.04 years. Twenty-seven patients underwent single-segment fusion; 21 underwent 2-segment fusion. No patient underwent ACDF at more than 2 levels. The mean F/U duration was 20.11 ± 7.87 months (range, 12.2–48.23 months). Patients were categorized into young-old (n= 30) and middle-old groups (n= 18). Table 2 summarizes the patient characteristics and comparative analysis results according to age group. ASA physical status classification differences were significantly different according to age group, but there were no significant differences in other factors.

Flow diagram depicting the patient inclusion process. ACDF, anterior cervical discectomy and fusion.

2. Radiological Outcomes

1) Preoperative parameters

There was no significant difference in the preoperative radiological parameters between the 2 groups except that SA was larger in the older adults group (p= 0.033). In Pearson correlation analysis, age had a weak correlation with TIH (r=-0.244, p=0.044) and SA (r = 0.296, p = 0.013), and the other factors were not correlated with age.

2) Postoperative changes

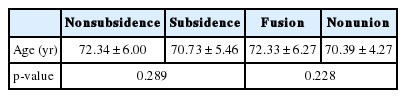

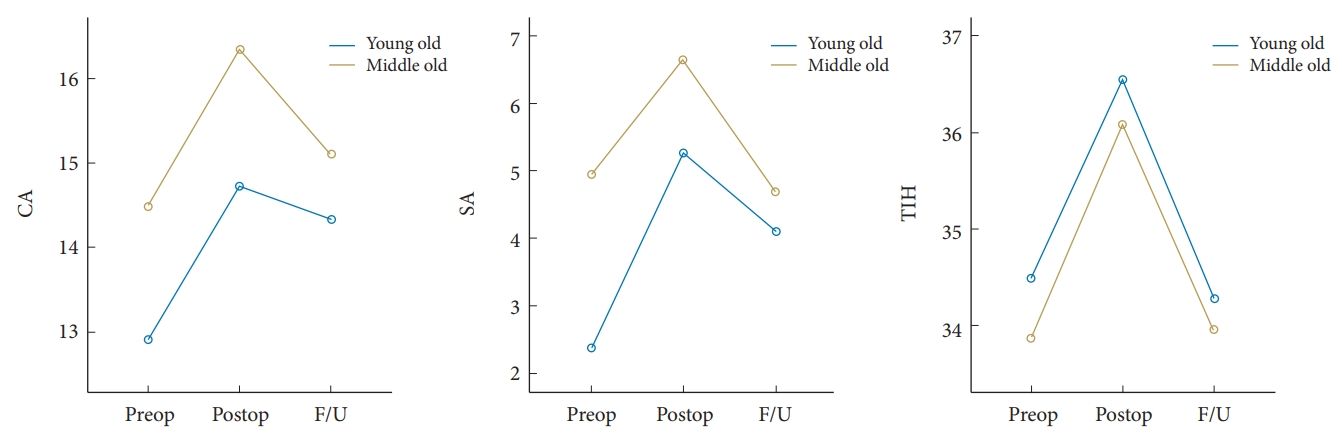

On the postoperative day 7, TIH and SA were significantly increased and CA did not show statistical significance (Table 3). However, these changes did not show any significant change from the preoperative results on the last F/U images (Fig. 3). There was no statistically significant difference in Δ for all parameters between the groups (Table 3). In addition, there was no correlation between Δ values and age. The incidence of subsidence and pseudarthrosis was not different between the 2 groups. Furthermore, there were no age differences according to subsidence or pseudarthrosis (Table 4).

Changes of cervical sagittal alignment according to age group after anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. CA, C2–7 cervical angle; SA, segmental angle; TIH, total intervertebral height; Preop, preoperative; Postop, postoperative; F/U, follow-up.

3. Clinical Outcomes

There were no significant differences in hand weakness and gait disturbance preoperatively between the 2 groups. In addition, there was no significant change in VAS (axial, arm), and NDI according to group. Hospital stay was slightly longer in the middle-old group but it was not statistically significant. Odom’s criteria were also not significantly different between the 2 groups (Table 5). In the young-old age group, there were no complications other than drug eruption (n = 1). In the middle-old age group, 3 complications were reported: Recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy (n = 1), screw loosening (n = 1), and pulmonary edema (n= 1) (Table 6).

DISCUSSION

The older population is increasing globally, and the interest of the medical community in this age group is also rising, especially with the increase in older people [12]. The World Health Organization defines the elderly as age 65 years or older [13]. As the aging process progresses, the number of the older population gradually increases and a more detailed classification is needed. Recently, older patients were subdivided into 3 lifestage groups: the young-old (65–74 years), the middle-old (75– 84 years), and the old-old (over 85 years) [14].

In our study, surgical spinal treatment was performed in the older patients, and the results of the study were documented. In particular, lumbar and posterior cervical surgeries are the most common treatment modalities, and postoperative outcomes are reported to be poor. Bydon et al. [15] reported the safety and efficacy of spinal fusion in the older population. Patients older than 65 years of age have significantly higher rates of complications after lumbar fusion compared with younger patients. Hayashi et al. [16] retrospectively studied 19 patients older than 80 years who were treated for lumbar spine disorders and found that the bone union rate was significantly lower and the postoperative osteoporotic vertebral fractures worsened the clinical outcome in patients > 80 years. In a similar study using the Nationwide Inpatient Sample to analyze the risk factors in 471,215 older patients undergoing lumbar laminectomy without fusion for lumbar stenosis, Li et al. [17] found that complication and mortality rates increased as patient age increased, and patients > 85 years old had a 14.7% complication rate and 0.22% mortality rate. Moreover, posterior cervical surgery showed similar results. Bernstein et al. [3] found that patients > 75 years old undergoing laminectomy or laminotomy were at higher risk of complication and mortality than younger patients. Veeravagu et al. [18] found that older patients (≥ 65 years) had a significantly increased complication risk following ACDF and posterior fusion.

The results of ACDF in older patients have not been reported so far. There have been reports of postoperative complications after ACDF in older patients, but there have been no reports of the clinical and radiological outcomes of ACDF. Buerba et al. [19] performed a study on 6,253 patients undergoing ACDF and found that older patients (65–74 and ≥ 75 years) were more likely to have blood transfusions, reoperations, urinary complications, extended length of hospital stay, and 1 or more complications, overall. In particular, patients aged 75 years or older were more likely to experience respiratory complications, central nervous system complications, or death. However, there is a limit to the description of radiological outcomes and spinespecific complications.

In our study, the clinical and radiological outcomes of ACDF were analyzed together with complications after ACDF surgery. Clinical outcomes were investigated as well as complications. The most worrying aspect of older patients is the occurrence of postoperative complications. In previous papers, the incidence of complications is increasing with age [7,19]. We investigated the occurrence of major complications in the previous study and postoperative complications occurred in 4 patients. There was 1 case in the young-old age, 3 cases in the middle-old age. Dysphagia is the most common complication in ACDF surgery, but not in this study [20]. This may be due to the fact that only patients who have continued to complain of discomfort and have seen additional tests and other treatments are considered.

One of the common complications, recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy, occurred in 1 patient and was spontaneously resolved within 3 months, postoperatively. In this study, left-sided approach was performed considering the anatomical location as one of the methods to reduce recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy [21]. There was no statistical difference between the 2 groups.

The parts we have observed particularly carefully are postoperative infection and mortality. Postoperative infection is known to be associated with an increased risk for older patients, which may increase the length of hospital stay and increase the incidence of other complications, affecting patient mortality [22]. In this study, the duration of antibiotic treatment was used up to 3 days after surgery and infection cases did not occur in both groups. In previous studies, mortality was higher in patients older than 65 years, and more in patients older than 75 years [23]. In this study, no deaths occurred in both groups.

This suggests that the incidence of complications is not high even in the elderly, there is no difference between the 2 groups. ASA physical status classification grade that evaluates systemic disease is related to the incidence of complications, but is not statistically significant and further studies are needed. In our study, no difference was found in the clinical and radiological outcomes of the middle-old patients compared to the youngold patients. Ultimately, even if it is older, if you are to be adapted for surgery, you can actively consider surgery.

Generally, as age increases, bone density and mass decrease with the changes in bone metabolism [24]. These changes may increase subsidence in ACDF patients, leading to decreased bone fusion rate, segmental kyphosis, and acceleration of adjacent segmental disease [25-27]. Lee et al. [28] reported that the main factor affecting subsidence is age; subsidence after ACDF induced lower fusion rate and poor clinical and radiological outcomes. In our study, however, postoperative sagittal alignment, subsidence, and fusion were not associated with old age.

The ACDF removes a compression lesion and increases the height of the neural foramen [29]. Certainly, ACDF generally has fewer muscle injuries, shorter operative time, quicker postoperative recovery, and minimal surgical risk [30,31]. When we synthesize our findings, ACDF can be safely performed in older patients.

This study has a few limitations. First, the study was relatively small and retrospective. However, it can be used as the pilot study for a study on older patients because there is not much access to older patients in a single institution. Second, there is a report that radiologic outcome varies according to cage type, the subsidence according to the cage type was not accurately compared in this study [32]. The need to use cages in accordance with patient specificity also limited our study; we believe that large scale and multi-institutional studies will help overcome this limitation. Third, the mean F/U period was too short to evaluate the long-term efficacy of the procedure. Moreover, F/ U of more than 1 year seems to be more meaningful because of the difficulty of regular outpatient treatment because of the low hospital-visit rate of older patients and because most of the subsidence and fusion occur in the 1-year period. Further large scale, prospective, randomized studies with long-term F/U periods are needed to overcome these limitations.

In conclusion, we analyzed the radiological and clinical outcomes of ACDF in older patients. There was no significant difference in the radiological and clinical outcomes between the young-old and middle-old groups. ACDF can be safely performed in older patients, but more, large scale long-term studies are needed to elucidate the findings of this study.

Notes

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a 2-Year Research Grant of Pusan National University.